On the merits of the Second Commandment

now all them jokers kept around, just like the scarecrows in hometown

Hello,

This is a personal, rambling essay that mentions a bunch of famous people being vile. Also, this is an essay about disillusionment, fame, temptation, and what to do next. I believe a general caveat lector is in order: we will discuss some progressively more and more unpleasant stuff. Also, there is some profane language. This is an emotional matter.

***This is a long post that might be truncated in emails. I highly recommend you click on the title to read the whole thing without interruption.***

1. Surely you’re joking, Mr. Brodsky!

It is a truth universally acknowledged that Joseph Brodsky, one of the greatest poets of the XX century, Nobel Prize recipient, and US Poet Laureate, was an asshole.

This is not a secret and shouldn’t be a surprise. Almost any memoir of anyone who interacted with Brodsky mentions this fact one way or another. Most often not explicitly, of course, but the stories they tell of him tell a bigger story. By many accounts, he was rude and inconsiderate to his friends and even worse to strangers, malicious to his enemies, and a horrible womanizer.

When I was younger, that didn’t bother me that much. Brodsky was always a beacon for me, as someone who dabbled in poetry in Russian, a symbol of what is possible to achieve in this language. He was, in many ways, my poetic role model, and his personal pugnacity seemed disconnected from his divine creations.

That is, until I started to read his poems carefully.

He was harsh in them as well, and rude, and straight away unpleasant. There is some nationalistic stuff in there, sometimes. There is some personal stuff as well. In “The Bust of Tiberius” (1981), he wrote, “All hail to you, two thousand years too late.//I too once took a whore in marriage.//We have some things in common.”

That was wholly unwarranted and did not have much to do with the rest of the poem. The “whore” in question was, of course, M. B., Maria Basmanova, his wife between 1962 and 1972, his muse throughout most of his life, a woman to whom he dedicated some of the most lyrical, soul-tearing poetry ever written.

Also, he dedicated this poem to her, the fragment of which I imperfectly translated below:

Twenty-five years ago you liked to sing, had an artist’s veneer, had a penchant for dates and lula, sketched in a pad with color, had your fun with me, then eloped with a chemical engineer and, as one can tell from your letters, have gotten terribly duller. 1989

The “terribly duller” jape is infantile and, as such, can be disregarded. But I was shocked by Brodsky’s ability to cram a decade-long history—a marriage, a common child, some shredded veins, tantrums, crazy drama (on both sides, I understand)—into the innocuous “had your fun with me.”

A genius, fully recognized, at the top of his fame, already a Nobel Prize recipient, he knew perfectly well that everything he writes will remain forever in the annals of history. And, almost twenty years after separation, this is what he chose to do. He immortalized her in these lines, just like he did in hundreds of others. She will never not be in these lines.

What a petty, vindictive piece of shit.

I was seriously affected by this poem (still, a genius-level poem, mind you—link to the original text) at the time. I think I was in my early twenties. It made me rethink some stuff about artists and their private affairs slowly seeping toxins into their art. Why on Earth would he do something like that? Why would an artist let that happen?

Brodsky remained my poetic inspiration, but he never became my personal one. I think this case helped me a lot going forward. It was a great inoculation—a disillusionment vaccine—before the first wave of MeToo struck and we learned so much about our idols we truly wish we hadn’t.

2. Surely you’re joking, Mr. Feynman!

This one cut in a different way. Brodsky could have been my artistic role model, but Feynman—one of the most celebrated physicists, Nobel Prize recipient, etc.—was never my scientific one. I am not a physicist, and my knowledge was never enough to deeply interact with Feynman’s science.

But he definitely was a personal inspiration. When I was in high school, he showed me that a scientist, a dork, could be funny, and mischievous, and self-assured, and overall a charismatic guy that is fun to be around. That a scientist is not just a kooky weirdo in a robe. That a scientist can have other quirky interests; he can be wider than his science. And I tried to model my behavior according to these ideas, which I, like many of my peers, learned from his famous book, “Surely you’re joking, Mr. Feynman!”

Which is why I got upset when I saw this excellent video by Dr. Angela Collier called “The sham legacy of Richard Feynman.”

Caveat: this video is 2.5 hours long. I do recommend watching it, though, if you, like me, enjoyed the book but didn’t reread it for a while. It is sometimes an unpleasant watch, but it reveals a lot about this book—and Feynman himself—that probably every fan of his should know. I will not recap the whole video, so this is your chance:

In the very beginning, Dr. Collier says, “I just think it’s kinda weird that the most famous physicist is known for his personality rather than his physics.” And I absolutely agree with her. This, upon reflection, is a seriously problematic point. Even more problematic, though, is that this personality might not have much to do with reality.

In the video, Dr. Collier dissects the “Surely you’re joking” book and the legend of the Richard Feynman character that emerges from this book. And, like any autopsy, it is unpleasant to observe. I still think that the biggest fault in this whole story lies with whoever came up with (probably, genius) marketing for this book, but the truth of the matter is that the book is not what it seems. I read it in high school under the impression it was an autobiography, written directly by Feynman himself. It is definitely presented as such: it is written from the first person, and the book cover has only one name. In reality, it is a collection of drunken tales told by Feynman over many evenings to his much younger friend and, possibly, an adoring superfan.

There is a huge epistemological difference between the two.

If Feynman had been a writer, it would have been fine. Or an actor, a director, a musician, a poet, a painter, a baker, a candlestick maker. But Feynman was a scientist, and science has a special relationship with the truth. He should have known better. And that’s what bothered me the most in this story. One of my role models turned out to be a made-up character.

Of course, the fact that Feynman might have been abusive to his second wife also didn’t help.

Why did he think it was ok to be so frivolous with the truth in his personal life? Maybe it was the contrast with his work, where he had to be truthful to a T. Maybe it was his way to unwind after a day of exceptionally high-energy mental work, just like the bongo drums or any other of his actual shenanigans. But maybe it was also the fame, the reputation he accrued, the adoration of younger men and women that eventually was built around his personality and not his physics.

Maybe he was a victim of his own creation.

Which, of course, brings us to our next joker.

3. Surely you’re joking, Mr… Oh, Neil, for fuck’s sake…

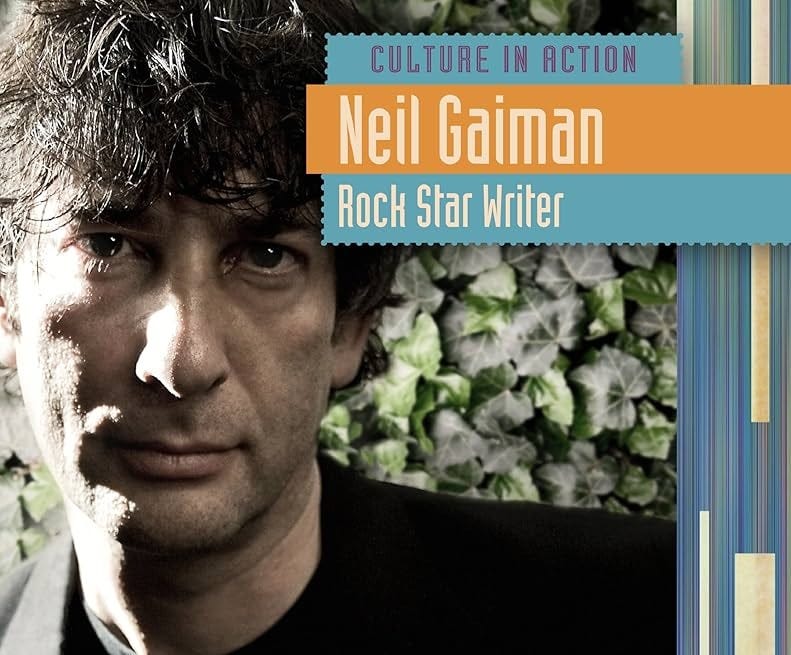

And of course, this essay mentions Neil Gaiman.

For many, many years, when asked who my favorite author was, I answered Neil Gaiman. Everyone liked Neil Gaiman those days; he was on this thin border between fantasy and serious literary stuff and an exceptional stylist to boot. There was no shame in mentioning him to your Grandma or in a school smoke corner. His own voice was light and funny, with just enough gravitas and darkness to make it interesting. Moreover, he was always so precise, so discerning; he understood the human condition and knew how to relay it on paper. He understood me, to a large extent. So, that always seemed like a good answer—with a lot of truth to it and absolutely non-controversial.

Well, that backfired, didn’t it?

One could say that Gaiman, unlike Brodsky, who was my artistic inspiration, and Feynman, who was my behavioral inspiration, was my “professional” inspiration. He was the guy I wanted not just to write like, but also to be published like. He did novels, short stories, comic books, children’s books, poems, TV scripts, essays, and blog posts, all with his trademark soft British humor, intelligent charm, and rock-star edginess. He wrote what he wanted, and everyone bought it, and his books were adapted for movies. There was a time when Neil Gaiman had it all.

Rock star is actually correct. Throughout all his career, Gaiman tried to act like one, from wearing all black to being friends with some, and in the end, marrying a proper rock star. Should we really be surprised if the most ugly part of the rock stardom also found its place in this elaborate cosplay? I am not going to retell the whole sordid story. Suffice it to say that Gaiman exploited his fame, status, and money to do unpleasant stuff to and with several women, not all of whom have been totally up for it or ok with it. On February 4th, he and his ex-wife were sued for alleged sexual abuse and human trafficking.

I am not angry anymore; I’m just disappointed.

Many people who wrote about this remembered Gaiman’s own story of the muse Calliope, who was kept imprisoned and repeatedly raped by a writer, thereby granting him inspiration for his novels. The phrase that everyone recalled from it was a response of the writer to one of the fans: “Actually, I do tend to regard myself as a feminist writer.” Of course, Gaiman’s protagonist was not this writer, but Sandman, a mysterious, black-clad figure who saved the muse and punished the monster.

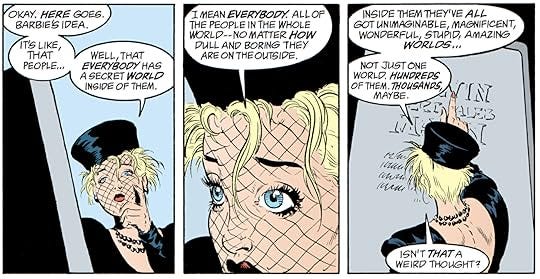

I remembered another quote of his, from another volume of “The Sandman,” and it is this one:

Everybody does have secret worlds inside of them. The trouble starts when they begin to leak out. Isn’t that a weird thought?

What possessed the man with such an understanding of the human psyche, such a firm grip on reality, to lose it so spectacularly? What force made him let go? What makes our inside worlds leak out of us when we become successful and adored by many? And why are there so many penises in them1?

4. Why are there so many jokers around?

Of course, it doesn’t end with these. One could remember Roman Polanski, Bill Cosby, Kevin Spacey, James Franco, Louis C.K. (with a certain asterisk),2 and many, many others. Hell, this sort of stuff is so common with musicians, the girls it happens to have a special name, “groupies.”

And I’m not even talking about specifically sexual stuff. General nastiness also applies here3. What makes these very smart and very talented people behave like assholes and, maybe even more importantly, like dumbasses? In the worst case, what makes them confuse their penis for their talent and try to jam it down our throats? And this is not a new phenomenon either, the common phrase “never meet your heroes” didn’t become common by a fluke.

Incidentally, here is a quote from Neil Gaiman: “I've met too many of my heroes, and these days I avoid meeting the few I have left, because the easiest way to stop having heroes is to meet them, or worse, have dinner with them.“

You see, he understood all that, and he still went crazy!

Well, there is a saying by Lord Acton: “Power tends to corrupt, and absolute power corrupts absolutely. Great men are almost always bad men, even when they exercise influence and not authority4.” Since we live in the internet era, we can feel the true predictive power of this saying with every new scandal. Power corrupts, and fame and adoration are a type of power. But fame and adoration are not given to them by gods or by the state; they are given to them by us, their admirers.

Are we to blame then for the inevitable corruption of those we love? Since I was anxiously waiting in line to get Neil Gaiman’s autograph at the ICon event in the year 200-somefuck, should I feel a tiny bit responsible now for him going apeshit from all the love and veneration he got over the years?5

Surely not. But also, maybe.

It is probably good to remember that this type of admiration, of idolization (and idealization) of a talented person, is slowly poisoning them. Our love, as it were, is toxic. My guess is feeling such a fervent, unconditional love and adoration from thousands and thousands of others must turn into a constant whisper inside the artist’s head: “You are good. You are great. You are better than anyone else. And they are worse than you, and you can do whatever you want with them because of that.” This is not a 100% healthy relationship that we have with our idols, and in it, we should show restraint, because they, sure as hell, will not. Love is a drug after all, almost literally.

What should we do, then? Maybe we should object more vocally to the idolization phenomenon in our society, to the fandom as a concept, to the “groupie” culture. It really sucks for everyone involved: potentially dangerous to the “idolizers” and toxic to the idols themselves. Maybe it’s time to go back to the Second Commandment: “Thou shalt not make unto thee any graven image […] Thou shalt not bow down thyself to them.” And not because “our Lord is a jealous Lord” (horrible reason) and not because it is written in the book, but simply because it’s unhealthy to do so.

And if we have to make a “graven image”, an idol—if it is necessary for our development to love a strange person unconditionally and use them as a role model—maybe let’s stick to made-up characters. When I was a kid, I really liked Sherlock Holmes—not the autistic Cumberbatch version, and not even the superior Soviet TV version, but the book version, in which Holmes was smart, and funny, and sometimes eccentric and absentminded, but he was also caring and kind. When I grew up, I stopped idolizing him, because it’s childish to look up to a made-up character. But is it? Was Sherlock Holmes so different from the version of Richard Feynman I looked up to afterwards?

Or, if we need creative inspiration, why not turn to writers of old? At least, there will be fewer surprises. Neil Gaiman was an exceptionally talented and successful writer, but I can think of another, of an author so successful, whose two main works became the basis of modern literature. And he managed to create them with a disability! Of course, I’m talking about Homer, the true rock-star writer.

Thank you, Homer! For forever enriching us with your art, and then for dying before we could know for sure who you were and what you did.

5. What should the poor fucking jokers do?

I decided to add this part after some deliberation. The main reason is that I, myself, have some writing ambitions. And that led me to think, what would I do in this situation? Let’s say, my book miraculously becomes popular, and I get to taste the poisoned but oh-so-sweet drink of fame and admiration. How would I deal with it?

I came up with three ways. There certainly are more; there are plenty of talented, universally adored people who are not sex-obsessed, crazy, or even assholes. There are plenty of very popular and also very nice poets, scientists, and writers6. How do they silence the whispers and fight the temptation? I am sure, one day, someone will come up with the Popular Artist 12-Step Program. For now, these seem reasonable to me:

1. Do a Pynchon

I will never forget a line from my conversation with a friend in the early 2000s. We were talking about a talented Russian-speaking sci-fi writer, who then was just a terrible person and now is a full-blown fascist. My friend said, “If I ever become a well-known writer, I will never have a public blog so that the world does not learn what a piece of shit I am.” Good advice, this.

This, of course, can be generalized to the overall relationship with the fandom. There is no real artistic need for it, it is just extremely pleasant. It is a cherry in top of the cake of being immensely talented. Some writers, however, remain recluses and never make public appearances of any kind—famously, Thomas Pynchon, but there are others, like J. D. Salinger, Harper Lee, Viktor Pelevin, Octavia E. Butler, Elena Ferrante. These examples are maybe a little extreme, but in general, as with any drug, practicing cautious, controlled consumption is a good idea. You don’t need a twitter, a tiktok, an instagram or whatever else they come up with next. Something simple, like Substack, might suffice.

2. Get a partner

One of the sad parts of the Gaiman story was the role of his wife, Amanda Palmer. I am sure she had the ability to give Neil a reality check, to tell him, “What you’re doing is bullshit, and you should stop immediately before you harm anyone.” But she didn’t; moreover, it can be argued that she enabled him and supplied him with women. This is not the type of partner I mean.

Many artists, however, have lasting marriages where both family members survive the onslaught of fame gracefully. I am sure, in such a case, they try to support each other and also keep each other in check.

This thing also should be discussed between the partners in the open. Not everyone would be ready to be the partner of a celebrity, and rightfully so. But constantly talking to another human being, who loves you but allows themselves to be critical of you, may be the best-known way to remain sane.

4. Recognize the responsibility

No amount of talent is an absolution from being a decent human being. In fact, one could argue that being a decent human being should be the price for being a gifted and universally adored person. Maybe even more harshly (and metaphysically), being a decent human being should be a price for having the gift in the first place. If you were given a talent, the least you can do is try not to confuse it with your penis.

That is not and never will be what most people are interested in.

You can also think about it this way. If you find a platinum vein or a diamond deposit in your backyard, you can profit from it, but you have to realize that part of it belongs to your country. If you are gifted with a great talent, you can profit from it, but you have to realize that part of it belongs to humanity. Or (again, going metaphysical) to art itself. Try not to poison it with your secret worlds.

Joseph Brodsky is still one of my favorite poets, and I read and try to translate his poems regularly. I will probably re-read Feynman’s “Lectures on Physics,” from which I learned a lot once, when I have a bit more thinking time. I will probably re-read Neil Gaiman’s books as well, and I will definitely read if he writes something about this surreal experience of his, about temptation, self-delusion, falling from grace, and finding oneself anew. If anyone can write about it, he can.

Yes, the artist is not the art, but they are forever linked, both during creation and after.

Best,

Ꙝ

My previous post on a somewhat related topic is here:

Should We Read Mein Kampf If We Really Really Want To?

Hello, A lot of people I talk to are going through the same moral conundrum. And it is not an easy one or a new one, either. Essentially, it boils down to a question: should I continue to appreciate art I like if the artist has become a Nazi (or has revealed themselves to be similarly morally repugnant)? After all, in the last two and a half years, the l…

in the spirit of gender equality, here and below, in some cases, the penis should be viewed as metaphorical

I am deliberately not including Weinstein and Munro cases here, as I think they are somewhat different phenomena from what I’m describing and from each other

Ellen DeGeneres, anyone?

which also makes one think about the word “influencer,” doesn’t it?

An important note here: when I talk about responsibility, I am not talking about fault. Whatever Neil Gaiman did, for instance, I wouldn’t blame anyone else other than Gaiman himself; the fault is with him. But it is quite often, when a crime is committed, for example, a robbery of a convenience store, only one person is at fault (the robber themselves), but many people have failed (institutions, parents, friends, etc.). All of these share a responsibility with the perpetrator, although they, of course, don’t share it equally.

and, I hope, also a couple of musicians and actors

Als Psychiater muss ich natürlich schmunzeln (wir lernen die Leute auch in ihren Unterhosen kennen, deshalb gibt's das Arztgeheimnis). Das ist der Unterschied zwischen der Person und ihrer Persona. Und Balzac hat den Unterschied zwischen "Charakter haben" und "Persönlichkeit sein" herausgearbeitet. Brodski war eben nur eine Persönlichkeit.

Can you elaborate more on the Feynman aspect?

I remember reading that love letter to his first wife and it's hard to imagine that person as also as horrible as it seems some of the others on your list are.

I guess I should just watch the video.

But I would love to see you do Tolkien, Hawthorne, Walter Scott for a counterpoint!

Maybe Bulgakov?