How to address a Russian: a comprehensive guide

this might be my least readable post but a few of you will say thank you

Hello,

I’ve been recently reading Arkady Renko books by Martin Cruz Smith. They are not bad: quite pulpy, but enjoyably so. There is relatively little of what Russians call “cranberry”—simplistic, stereotypical Western depictions of Russian life, vodka-bear-balalaika style. Overall, I would say Martin Cruz Smith has decent Russian advisors and fact-checkers.

There is, however, an issue with the books, which is a pet peeve of mine. There is a prominent character in the books called Tatiana Petrovna, and she is not a Russian Empress and not a 90-year-old granny but a young journalist. My Russian readers are probably snickering at this point, but the rest don’t even know why.

***This is a long post that will be truncated in emails. I highly recommend you click on the title to read the whole 3000-word post without interruption.***

To be fair, almost every non-Russian writer who includes in their books a Russian-speaking1 character makes a similar mistake. What I mean is the mess with Russian-style names, a thing that is incredibly natural to me but seems impenetrable to non-native speakers. And justifiably so, I would say: when you begin to think about it methodically, the amount of nuances in how Russians address each other is staggering.

So, this is a guide for everyone who’d like to put an alcoholic chess master, a circus bear wrestler, a babushka, a model-turned-assassin, or an even less cranberry Russian character in their book.

1. The second-person pronoun

Before we even go to names, there is an issue of a pronoun, and not the usual one. Russian has two second-person singular pronouns: a singular you, ты, and a plural-but-used-as-singular you, вы (not unlike ‘du’ and ‘Sie’ in German or ‘tú’ and ‘usted’ in Spanish). The first is suitable for either friendly, informal occasions or to stress the difference in status of the two people talking: a czar, for example, would address his subjects as “ты”, their familiarity notwithstanding. In addition, singular you is often a sign of a rude or a provincial person. The ‘PBUAS you’ is used between people who don’t know each other that well or to stress the respect towards the addressee.

But even that is not a full picture, because there is also a capitalized form “Вы”, which conveys even more respect than a normal “вы”. It is only used in writing and is considered archaic, but if your jam is translating some XVIII-century Russian epistolary prose, you should be very aware of it.

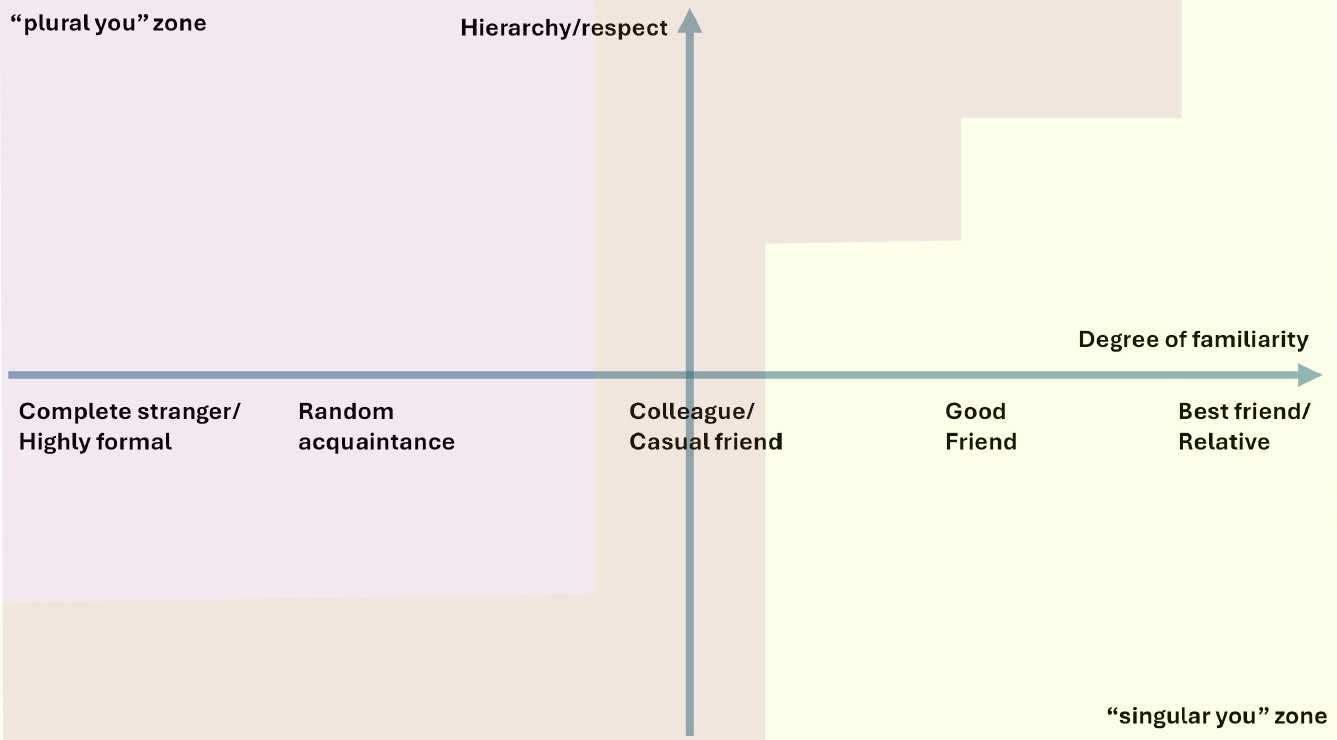

I will give you a graph of using the second-person pronoun on a familiarity-hierarchy scale, partially to illustrate my point and partially for you to get used to these axes, since we will return to them again.

2. The three names

All Russians have three names: a first name (N), a patronym (P), and a family name (F). Unlike with the western-style middle name, the patronym is obligatory and is assigned at birth without much deliberation; it is a derivative of the name of the child’s father.

The only two correct forms of the full three names are NPF (Lev Nikolaevich Tolstoy) or FNP (Dostoyevsky Fyodor Mikhailovich). The first is mostly used in conversations, and the second—in writing, although this is not strict and depends mostly on the environment. The FNP structure is more formal. A good example is this Wiki page, where both forms are used one after the other: the title of the encyclopedia article is FNP (among other things, easier to alphabetize), but the text begins with a smoother-to-read NPF.

However, keep in mind that NPF is almost never used as an address to a person, and FNP can be used, but in a very formal situation, like reading from a list or a general announcement: “FNP, FNP, please approach gate 7, your flight is boarding.”

This is all fine. The problem with Russian addresses begins when you realize that almost all other combinations of N, P, and F are also permissible and used in different circumstances. Let’s try to catch them all: only N, only P, only F, NP, and NF are all common (and not exhaustive), and they all mean something: you cannot switch one with the other without screwing up your tone or your intention. This is where all the nuances lie, and this is where we’re going.

3. First name

Obviously, calling someone by just their first name, N, is an informal address. In the past, an address by the full first name was unthinkable, but today it is perfectly common, even between strangers (but they have to be roughly of the same age/hierarchical status). Even though this part is the same as in English, Russian first names, in my experience, can be quite confusing to non-native speakers.

The trouble with the first name comes from the fact that Russians like long and beautiful names, but in conversations they like to immediately shorten them. This is not different from Robert/Bob, William/Bill, Catherine/Kate, Elizabeth/Beth, etc.

The difference in the Russian language is, probably, that 1) almost every name has a diminutive and often more than one (just like Elizabeth can be Beth, Lisa, Lizzy, etc.), and there is much more emphasis on familiarity/formality scale here. For instance, I can address my business partner Robert California simply as Bob in English, especially if he introduces himself as such, but calling Dmitry Medvedev simply Dima, or even worse, Dimon, can be considered an offense unless we are close pals. One of Navalny’s most efficient corruption investigation’s title, “He Is Not Dimon To You”, stressed exactly this nuance in Russian language.

For the purposes of this guide, I will designate uppercase N to mean “full first name” and lowercase n to mean “some diminutive of the first name”.

If you don’t know for sure, how do you form the shorter names? There is, unfortunately, no good answer. Most of them are derived from dropping some letters and shortening and softening the end of the full name (Konstantin→Kostya), some drop first letters too (Ivan→Vanya), some add/change a suffix (Pavel→Pavlik), and some are historic and don’t make sense (Alexander→Sasha/Shura (what?)).

Unfortunately, that’s not all. There is also a second-level diminutivation, used either between kids, very friendly adults, or close relatives. These are often formed by the suffixes [-k-/-‘k-], or by the suffixes [-echk-/-ushk-/-yush-/en’k-/-un’-]. So, a close friend can call Alexander not just Sasha, but Sashka, his grandmother can call him Sashen’ka, and his girlfriend can call him Sashun’a. These are all more optional, really personal, and depend on personal preferences. Those super-diminutives we will call nn.

Another, thankfully archaic use of n and even nn is an address to a serf.

4. Patronym

First, there is a special form of address by the patronym P only (i.e., Petrovich). It is highly specific: it is used only between adult friends and is associated with more provincial, simple-speak. Two neighbors in the village can call each other by the patronyms. If two neighbors in the city do that, it implies either their advanced age or some level of tongue-in-cheek (more on that horrible subject later).

Name+Patronym (NP) is, on the other hand, a very common address. It is used between people who have been introduced but are not friends; in most formal situations; in conversations with much older close friends. It is a high-respect, low-familiarity way of addressing. It is exceptionally common in Russian classics and did not go away in either the Soviet period or the new Russia (although the latter two are much less formal). If you need to address an unfamiliar Russian in social circumstances and do not want to offend them or embarrass yourself, NP is most likely the way to go. If you don’t know the person’s P, a polite way is just to ask: “what are your name and patronym [imya-otchestvo]?”.

Another niche use is addressing the Czar/Czarina/any member of the royal family: always NP, never F.

But most non-native speakers get in trouble when forming patronyms. There is where poor Tatiana Petrovna from the second paragraph comes in. The problem is that for an untrained ear, it is very easy to mix the patronym and the family name (and in some cases they are indistinguishable). Let’s try to clear the waters.

For males, the patronym is formed by using the suffix [-vich-]2 (i.e., Ivan Denisovich). For females, it is [-vn-] (i.e., Matryona Vasilievna). Patronyms are formed from the language of belonging to someone (i.e., Petrovich is Petr’s son), and that “v” is analogous to “‘s” in English.

Now, the confusion stems from the fact that, just like in English and many other languages, there is a common family name type, formed from the first name of a male. In English, Johnsson is John’s son. In Russian, Petrovich is Petr’s son, and Petrov is Petr’s son; only the first is a patronym, and the second is a family name. Analogously, Petrovna is Petr’s daughter, and Petrova is Petr’s daughter; but the first is a patronym, and the second is a family name.

For males, “ich” is a good indication of a patronym. There are family names with the same suffix (i.e., Rabinovich, a common anekdoty character, or Abramovich, a well-known oligarch), but they are quite rare3. A yet additional complication, is that sometimes patronyms are shortened from “-ovich” to “ych” (Rodion Romanovich→Rodion Romanych). This is indicative of the addressor being either rural, or very closely familiar to the addressee4.

For females, the difference is even more subtle for the ear, between “vna” and “va” or “na”, which is another common ending of a Russian female family name. You have to have both “v” and “n” for it to sound like a patronym5.

Our literature teacher in Hebrew-language school was reading us ‘Crime and Punishment’ and was always making the same mistake: she was calling Sonya Marmeladova’s stepmother6, Ekaterina Ivanova. We told her: This is a mistake, and she should be Ekaterina Ivanovna. Aah, said the teacher, just like in Anna Karenina?

Nope. And if you now understand why, you are in a good spot.

To summarize: you should use patronyms. They are most often signified by [-vich-] for male and [-vn-] for female names. If you’re not sure or getting confused, make a simpler name for your character (and their father!), goddamit.

5. Family name

The address by the family name alone is an important one because it is almost always addressing someone hierarchically lower. This is used to reprimand and to diminish. A teacher might call a student by their family name if they’re misbehaving; a superior might call their subordinate by F if they are not happy with their performance. A civil servant might call that a visitor to put them in their place.

Another special, formal, and non-offensive way of addressing someone is “title+F”, but that is mostly archaic. In Czarist Russia, the title could have been “mister / missus / miss / monseigneur / madame / mademoiselle / milord / milady / etc.”, followed by the family name. In Soviet Russia, it was mostly “comrade F” (for both male and female addressees). In modern Russia there is a notion to get back to “Mr./Mrs.”-type titles, but I don’t think they’re common and seem too formal to the level of disingenuity. Titles like “Dr./Prof.” are used like in English, typically with the F only, and primarily in the most official way. For instance, one could address their doctor for the first time as Dr. F, but then switch to NP.

The form NF is almost never used in a direct address and only in conversations about the third person or when announcing someone (“And the Matryoscar goes to…”). There is also a rare variant of that, nF, diminutive+family name, and it is used exclusively in schools, when discussing students (“Kostya Asimonov broke a window with a math book today”).

6. Putting it all together

So, as we already discussed, the two main parameters for choosing a correct address are “familiarity”—how close you are to the addressee—and “hierarchy/respect”—how much reverence you would like to convey or where in the social hierarchy do you want to put this person. A mistake on the “familiarity” axis often feels weird, and a mistake on the “hierarchy” axis—offensive. A rule of thumb is “when you’re not sure, use NP”.

That said, here is a graph. It is a mess. I struggled with the balance between comprehensiveness and clarity, and it is still a mess. The graph is divided into four quadrants: top-right (I) is for a person you know well and want to show respect for. It is a ‘grandfather’ quadrant. Bottom-right (IV) is for someone you know well and don’t try to show respect for. It is a ‘buddy’ quadrant. Top-left (II) is for someone you don’t know that well, but who is higher in the hierarchy than you. It is a ‘boss’ quadrant. And bottom-left (III) is for someone you neither know that well nor respect. It is a ‘minion’ quadrant. I also removed all the anachronisms for clarity’s sake, so, for instance, for the XIX century, you would need another graph.

The graph is a mess because I’m bad at drawing graphs. But the graph is a mess also because the language is a mess.

To use this graph effectively, you need to define the relationship between the two characters, decide on personal preferences for both of them, understand what does the addressor want to convey to the addressee in this particular moment, and then go to the corresponding point in the graph and pick the option that is most suitable based on their personal preferences.

And this is something Russians do all the time in their heads. No wonder so many of them become alcoholic chess masters.

7. Irony and sarcasm

This was exhausting, but even this is not the full story, or, rather, is only one side of this hellish icosahedron of a story. Russian is a high-context language, which means that there are clear rules, and then there are a thousand ways to break them, and the whole point lies in the resulting shatters.

I was discussing this with my wife (we call each other by n, by the way; we both dislike the nn address), and together we found several examples of deliberately “wrong” addresses. Some used for mockery, some to be tongue-in-cheek, some used as an inside joke, to stress the unique relation between two people. Here are a few examples:

some of my wife’s friends call her by P;

some of mine call me by F;

my wife’s parents, in early stages of courtship, called each other by NP;

one of our friends calls her husband by F;

kids at school, especially close friends, like to call each other by F;

alternatively, when someone wants to bring their opponent down, they can call them by n, nF or even nn;

however, a possible way of addressing someone familiar but clearly hierarchically lower than you is “plural you+n/nn”. A classic example is a professor with their student or a younger, less experienced colleague. In this case it is not meant to be derogatory, quite the opposite, a term of endearment;

even more basic rules can be broken in the name of irony: one of the most common denigrating nicknames for an infamous Russian blogger is Tatianovich, which is not a patronym but a matronym, derived from the name of his real-ife (also famous) mother;

this seems postmodern, but isn’t actually an invention of our times: one of the Princes of Galicia (1187) was nicknamed "Nastasich", for being an illegitimate son of Prince Yaroslav Osmomysl by his mistress, Nastaska;

…and so on, and so on.

We continued to discuss this issue for a bit, and the main question emerged: do we actually need all this bullshit? Patronyms, titles, diminutives, etc.? This hierarchical, formalistic thing in our language that is, in its origin and essence, oppressive? Doesn’t that affect the way we think about other people, imprint the hierarchy into our heads? Doesn’t it put us in this language cage and make us submit to each other through addresses?

Probably, it does.

Should we abolish it then?

Perhaps not.

Because only the existence of rules makes it possible to be a rebel. Because the beauty of a language lies in the complexity, in the thousands of facets and nuances of sarcasm, irony, affinity, and kinship that only a stringent rules system can create, and we, as humans, can defy and make our own.

Because the best jokes are inside jokes, and the deeper they are hidden, the more precious they are.

Best,

Konstantin Dmitrievich

I had so much trouble with this definition. “Russian-speaking” here does not necessarily mean Russian; it includes Ukrainian, Belarus, post-Soviet, generally Slavic, etc. This is a wide and blurry definition, and for that I apologize in advance. For the rest of the text, I will use the umbrella term “Russian” here, but don’t attribute it to my nationalism, please.

There are exceptions like Ilyich or Kuzmich (no “v”, just [-ich]), but as far as I understand, this is just for a better sound.

But other Slavic nationalities, especially those in the Balkans (i.e., Goran Bregović), have plenty of “iches” in their family names! Here, a letter ć might help you: it is traditionally not used in transcribed Russian names. It is also a very common ending in many Polish and Jewish family names (many thanks to

for this addition).Of course, there is yet another thing. Because of some older male names, some female patronyms end in [-ishna], [-inishna], or [-ichna], for instance, Vera Savvishna. These are increasingly rare and either archaic (think Czarist Russia) or closely related to Russian Orthodox tradition, where such names still exist.

Konstantin Dmitrievich, this essay is both thoroughly informative and highly entertaining, well done! It takes a bit for us foreigners to get acquainted to the intricacies of Russian formal and informal ways of addressing people. Could I make a pedantic remark, though? Raskol'nikov's mother's NP is Pul'cheriya Aleksandrovna; Ekaterina Ivanovna is Sonya Marmeladov's stepmother. My Russian NP would be Порция Иманнуиловна, which sounds очень смешно, as I'm painfully aware.😩

This was really interesting and your English is really good.

You have taught me a lot in this, mostly not to have Russian names in novels now. Jk.