Hello,

This is a post in the “No Oblivion” series, dedicated to books that I love but that are overall unknown, especially in English. My last essay in the series was about "The Tale of Hodja Nasreddin”, an incredible book that can probably be considered “young adult”. Today we will go deeper into childhood.

What is the best postmodernist novel?

It has to be “Pale Fire”, right? The unique structure, a framing device inside a framing device, an unreliable narrator? Or, alternatively, it certainly has to be “Gravity’s Raibow”, with its unconventional plot and subversion of traditional characters, with satire and humor. Or, or, it surely has to be “Infinite Jest” with its hundreds of characters, dosens of plot lines, turns, twists, and pivots all tied up in an extremely complex labyrinthine bundle of loose threats, that somehow still form a coherent picture. Or, maybe, it is…

What is the best postmodernist novel for children?

Um…

Yeah, not a simple question, right? But to me it is, because to me it has a simple answer, and that is Grigoriy Oster’s “Tale with Details”, a book that, while remaining a brilliant, engaging, and easy-to-read children’s book, somehow has all the elements of a postmodern novel that I mentioned above. And that, to me, easily puts it in the same row as other masterpieces.

So, let’s talk a little bit about this book, and let me convince you that Oster should be considered one of the greatest masters of postmodernism of our time simply because he chose the absolute hardest audience for his book and still admirably succeeded.

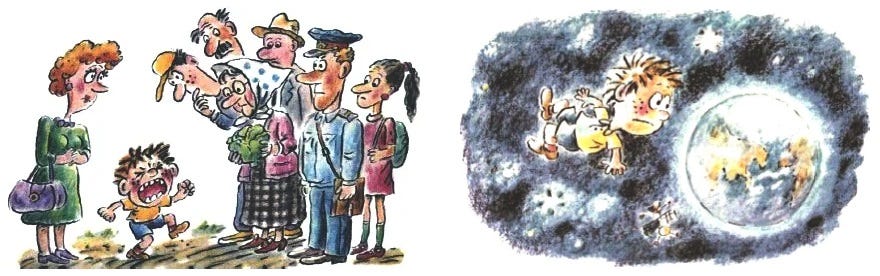

I haven’t found a translation of this book into English anywhere, so I took it upon myself to translate a few fragments. As usual, blame all the less-than-perfect stuff on me. In addition, I am using original illustrations by Eduard Nazarov from the 1999 edition.

So, let’s peel this book like a delicious onion (yes, onions can be delicious; you just need to know how to cook them). The top layer happens at an amusement part at the end of shift, when all the little horses from the merry-go-round (they are called Masha, Dasha, Sasha, Pasha, Glasha, Natasha, and Prostokvasha, which is Russian for tart buttermilk) are tired and ask the park manager to tell them a fairy tale, like he does every night. But the manager tells them that this is his last tale; he already told them every tale he knows but one.

His last tale is about a boy named Fedya and his mom, who took him to the zoo. Fedya wanted ice cream, and his mom refused because he had a sore throat. That prompted a scandal, during which he bullied a family of elephants, picked on the monkeys, was rude to an old lady, and then to a young policeman, and then he ran away. First, from his mom; then, from the zoo; then, from the city. At the end, he ran away from Earth altogether.

And then something wonderful happens.

"Wait!" Prostokvasha interrupted the manager. "Now Fedya's mom will zoom there on some rocket, forgive everything, and take him home, right?"

"Yes," said the manager. "How did you guess?"

"Moms forgive," sighed Prostokvasha. "It always ends that way. And yet, this is the last fairy tale. Could you," she asked, "not finish it just yet. First, remember some details."

"Didn't I tell it in detail?"

"Not really. For example, the old lady and the young policeman. You didn't tell us their names."

"The policeman's name is Ivan, the old lady's is Marya," the manager smiled.

"Ivan and Marya. Beautiful names. They go well together," Prostokvasha quickly said and glanced slyly at the manager. "Maybe they met—the policeman and the old lady? After Fedya ran away. And then something happened to them? Some details?"

This is how the real book starts. At the end of each chapter, the horses ask about side characters, and the next chapter features them. That creates a rather complex and interconnected web of characters, each of whom has their own stories and arcs. The manager lets horses choose which character thread they want to follow. Here are some of the characters:

Matwey the goat and Byasha the sheep, who is in love with him;

Rhinos numbers one, two, four and three;

An owner of the sweets shop who wants to find the person who wrote him a bad review and runs around the city, asking everyone to write something in his book of complaints to compare the handwriting (it were the Rhinos ## 1, 2 and 4);

The Editor-in-Chief of a children’s magazine struggling with a new issue;

Petya and Katya and their absolutely bonkers parents;

A bunch of school kids and another bunch of pre-school kids;

Little Monkeys and their Mother Monkey;

Two crooks, Spire and Dome;

A Tame Tiger;

The poet Pampushkin, who was so good, he got a huge monument built in his honor, and now everyone thinks he’s long dead;

and many, many more.

All of them live and interact in the single universe of the book, resulting in one of the most weird and entertaining tales I’ve ever read. Yes, with a lot of details.

Maybe the most impressive thing is that Oster never loses control of the narrative. His framing device, the merry-go-round horses, can stop the action at any time, being either too excited or afraid for the fate of the characters, but what feels chaotic and random at the beginning in reality leads to a very tight plot, where every little arc gets resolved and every question gets an answer. Except for those that don’t, because absolutely by design, the “Tale with Details” is infinite, and every plot resolution can have its own new and new details to look into. The book ends the following way. (I could have given a spoiler warning here, but there really is no point; you see, I won’t reveal the details.)

The amusement park manager looked up and saw that Prostokvasha had turned quite pink. Dawn was breaking over the park where the merry-go-round with its horses stood. A big, round sun was rising into the sky. In its rays, white Prostokvasha seemed to turn pink, and orange Sasha and Pasha became even more orange.

"It's morning already!" thought the manager. "Soon the children will come to ride the merry-go-round. Time to turn on the motor."

And the manager said:

"Night has fallen. Everyone has gone to sleep."

"What sleep?!" gasped Prostokvasha. "I didn't expect it from them."

"You should have! Sleeping is very good for you. At least occasionally."

"Wait!" Sasha and Pasha sighed. "Tell us just a little bit more. Just a tiny bit. What did they all do before going to sleep?"

"They brushed their teeth! And washed their faces."

[…]

"Oh!" suddenly screamed Prostokvasha. "And Fedya? The boy who jumped off his home planet. Is he also asleep?"

"He's asleep. Everyone in the city was asleep, and no one saw the rocket whizzing through the sky. The rocket landed, and out came Fedya's mom, holding her tearful, sleeping, forgiven son in her arms. Mom brought Fedya home, undressed the sleepy boy, tucked him into bed, touched his forehead to check if he caught a cold in the void, then sighed deeply and went to sleep herself.

"That's it!" said the park manager. "Now everyone's asleep! I won't list them all, but assume that everyone you can think of is sleeping. And the fairy tale is over. After all, mom forgave Fedya. And I've told you all the details. There are no more left."

The manager looked around. The warm morning sun was already shining brightly! Children who had just had breakfast were running through the park. The manager rushed to turn on the motor. The fastest children were the first to jump onto the horses. The carousel started moving. The horses raced around in circles.

"What a pity!" Sasha and Pasha sighed softly. "It's a pity there are no more details left."

"There are! There are!" Prostokvasha cheerfully shouted, picking up speed. "In the zoo, when Fedya was talking nonsense, there was also a female elephant with her baby elephant. Let's ask what happened to them this evening."

For a while, I could not understand the secret of the “Tale with Details”. How can such a complex book be so approachable to children? Is it just the author’s talent? Or is there a secret? This question bugged me for a while, and I couldn’t finish this essay. Until, one day, I could.

For absolutely unrelated reasons, I remembered myself, age seven or eight, playing with Legos. There are two types of people who play with Legos: the first type builds, and that in itself is the fun part; for the second type, the building is just decorations to play out scenarios with the Lego characters. I was 100% the second type. Of course, I cannot remember the exact plots that ran through my head when I held little plastic cowboys or pirates. But I do remember that they were rather chaotic: the plots would split and derail, new characters could come in, my focus would switch, cowboys could be attached by knights or ghosts, and pirates would get their ship to a gas station to fuel it in between raids. My games with the Lego characters were postmodernist in nature!

And I believe it’s not that unique. Kids do enjoy crossover stories; they do enjoy many characters and complex, more serious plots. If you need proof, take a look at the box office of the last good Avengers movie. Postmodernism is even not an invention of our jaded time; it was always here, hiding in the intricate tapestry of the “One Thousand and One Nights”, Greek myths or Icelandic sagas. They also have all the characteristics of a modern postmodernist novel. Chaos is inherent in human beings. Jumbling things up is natural and fun.

Putting it back together in the end takes a true master, and that is what Grigoriy Oster is.

If there is a children's book that deserves a translation to English, wide-spread success, and a place in eternity, it’s “Tale with Details”.

“Tale with Details” is not even Oster’s most famous book in Russian. He’s probably most known for his collection of children’s verses, “A Book of Bad Advices”, which are short humorous poems with intentionally (often hilariously) wrong messages. When asked why I like to write about books that, realistically, very few non-Russian-speaking people will ever read, I always remember this one:

The most crucial thing in your life Can be any utter nonsense. You just need to know firmly: There can't be a task more vital. Nothing will stand in your way then, Neither snow nor rain nor heat, and You’ll be gasping with amusement, Doing stuff you love the most.

Best,

K.

Great story (original) and great retelling -- thanks! (And I’ve always agreed that post modernism started long before modernism became modern!)

What an enchanting story.