Hello,

Like many Soviet and post-Soviet kids, I read Alexander Belyaev’s books in my early teens and then promptly forgot about them. I mean, they were fine. Very romantic, saccharine, and very… outdated is not exactly the right word. But definitely more children’s literature than (as I wanted to read then) “grown-up stuff.” Think more Jules Verne and H. G. Wells than Clifford Simak and Robert Heinlein. Belyaev’s claim to fame was being “the first Soviet sci-fi writer,” and in the 90s that was already deeply uncool.

I recently stumbled upon his biography, and I have to say, that made me revisit my feelings toward his novels. (Context is king, after all.) Because Alexander Belyaev might have been the first Soviet sci-fi writer, but he was also no less than a modern-day Job.

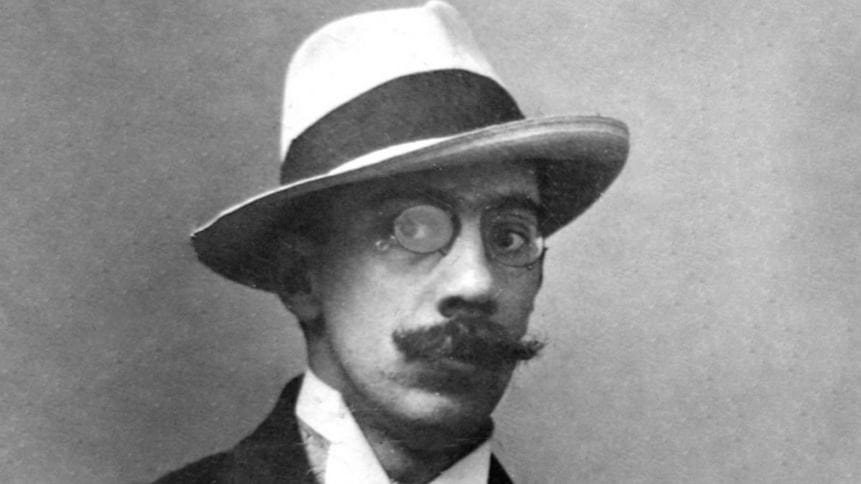

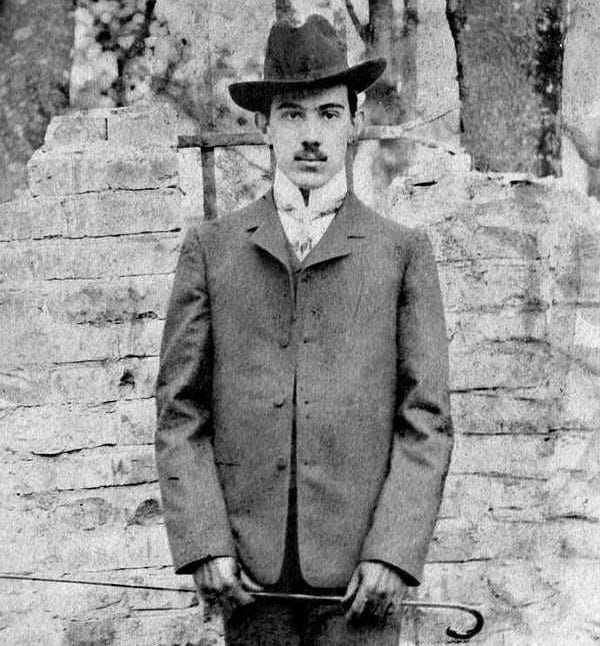

He was born in Smolensk in 1884 in the family of an Orthodox priest. He had two siblings—an older brother and a younger sister. Alexander was an active and curious child. He taught himself to play the violin and piano, was fond of photography and painting, and read a lot. His favorite author was Jules Verne. Belyaev consumed adventure novels and then tried to recreate the amazing feats their characters performed. One accident led to a trauma of his eye, resulting in partial blindness. Another time, trying to fly, he jumped from the roof and injured his spine.

You know that when a person dies, his senses do not vanish at the same time. First a person loses his sense of taste, then his sight goes out, then his hearing.

Alexander Belyaev, "Professor Dowell's Head", 1925One after another, he lost both his siblings: his younger sister died of sarcoma, and his older brother drowned. Soon after that, their father died as well, and Alexander had to provide for his family. He constructed scenery for the theater and played violin in the circus orchestra. After finishing his studies, Belyaev worked as an attorney but never truly enjoyed it. He also acted, directed, and wrote plays for the local theater.

Eventually, he was noticed by a legend of Russian theater, Konstantin Stanislavski (yes, the one with the method), who offered Alexander a place in his troupe. Belyaev refused. It is not clear why, but I think it was love: Belyaev got married soon after that.

That marriage lasted for less than a year. His wife left him for someone else.

It's easier to find a familiar fish in the ocean than a person in this human maelstrom.

Alexander Belyaev, "Amphibian Man", 1927Onwards and upwards: in a few years, Belyaev got married for the second time. But in 1915 he received a terrible diagnosis: Pott’s disease, also known as tuberculosis of the spine, a horrid echo of his childhood trauma. He was paralyzed from the waist down and spent three years confined in gypsum. His second wife left him, and he was taken care of by his mother. The only things he could do were read, and learn, and write. This is when he started to write sci-fi short stories and novels.

His mother died in 1919, died a horrible death: of hunger. Belyaev, still bedridden, could not even attend the funeral. In the same year, he married his nurse, Margarita. In 1922 he felt better and began to walk. He had to wear a special corset for the rest of his life: an actor and a looker in his youth, now a cripple. But, despite everything—happy.

On earth at night there are only small, distant stars in the sky, sometimes the Moon. But here there are thousands of stars, thousands of moons, thousands of little multicolored suns burning with a soft gentle light. A night in the ocean is incomparably more beautiful than a night on land.

Alexander Belyaev, "Amphibian Man", 1927He wrote more and began to publish. Short stories first, then novels. He also wrote essays, discussing the special mission of Soviet, socialist science fiction literature. For the next ten years he struggled to be a professional writer, finding odd jobs around the country. A new genre was not easily accepted by the state. He refused to write about “kolkhoz” and “reclamation of tselina” (which arguably were even less scientific). He believed in science fiction and clawed his way to publication and recognition, fighting not just for himself but for the genre as a whole.

A writer working in the field of science fiction must himself be so scientifically educated that he is able not only to understand what the scientist is working on, but on this basis to foresee consequences and possibilities that are sometimes not clear to the scientist himself.

[...]

It is also very difficult to establish the right proportion between scientific and narrative material. A plot that is too entertaining distracts the reader's attention from the scientific content, a sluggish plot can push the reader away from the book.

[...]

The plot of the Soviet science fiction novel must be built on the assumptions: classes have been destroyed, and the remnants of capitalism are gradually being eradicated from consciousness. There is no antagonism between the city and the countryside. The difference between physical and mental labour is increasingly smoothed out. What is the plot to be based on in a classless society?

Alexander Belyaev, "Let's create Soviet science fiction", 1934In that time he and Margarita also brought two daughters into this world. Unfortunately, they could not escape their father’s curse. One of them, Ludmila, died of meningitis at the age of six. The other, Svetlana, got sick with tuberculosis, which resulted in rickets. Just like her father, she struggled with her illness for the rest of her life.

But he did it! He got published, and he got recognized as a Soviet sci-fi writer. A trailblazer, in fact. So before we get to the last chapter of his life, let’s take a look at some of his novels.

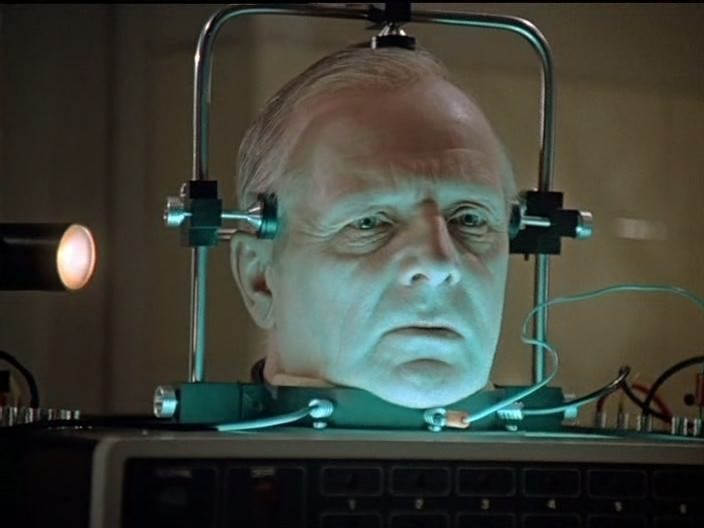

Professor Dowell's Head (1925) is a story of two scientists working on preserving life in separated body parts: a mentor, Prof. Dowell, and a pupil, Prof. Kern. The pupil gets jealous of the mentor and kills him but keeps his head alive to guide him in further research. Kern’s new assistant, a trained nurse, and Dowell’s son uncover this plot and bring Kern to justice. Dowell’s head, however, cannot be preserved, and the professor dies in the end. Belyaev himself wrote of this novel: “Illness put me for three and a half years in a plaster bed. This period was accompanied by paralysis of the lower half of my body. And although I had control of my hands, my life was reduced during these years to the life of a head without a body.”

Amphibian Man (1927) is probably Belyaev’s best-known work. It is basically a star-crossed lovers story between a poor but beautiful Guttiere and Ichthyander, a boy raised by a mysterious doctor, Salvator, after a life-saving operation: transplanting a set of shark gills. This scientific miracle allowed him to swim underwater without needing air. The fish-out-of-water story here is literal. The antagonist is a greedy pearl merchant, Pedro Zurita, who is in love with Guttiere and wants to exploit Ichthyander’s incredible ability. There is a fight with a colony of giant squids, it’s awesome. In the end, Ichthyander understands that he will never be able to live alongside people and chooses life under the sea.

Ariel (1941) is a story of Ariel, an orphan boy who could fly. He was given this ability by a couple of scientists who experimented on children in an Indian orphanage using “controlled Brownian motion”. The first thing Ariel does when he realizes he can fly is escape the orphanage with his best friend. He travels India and finds other friends and a girl he likes. Then, there are many adventures: Ariel gets captured by an evil Raja, works in a circus and even meets his sister, an heiress to a British lord. He lives with her in Britain for a while but, in the end, gets tired of British snobbishness and racism and runs away back to India to live with his friends and his loved one.

Ariel was Belyaev’s last written novel. You see, it was published in 1941, and there is a causal link between these two facts. The Second World War was in full swing, and German forces had reached Pushkin, a small town near Leningrad, where Belyaev and his family lived at the time. Having two family members with limited mobility, they refused to evacuate with the Soviets and remained under the occupation. Unfortunately, Belyaev’s wife, Margarita, was wrongly considered to be of German descent. She and her daughter were taken to Germany as “Volksdeutsche”, and kept there until the end of the war. After their return to the Soviet Union, they were immediately sent (an internal exile, a common Soviet practice) to Siberia, where they spent the next 11 years.

Belyaev himself, however, did not live to see that. On the next day after their forced departure to Germany, he died from hunger and cold. As his daughter Svetlana has put it in her memoirs, “My father had eaten little before, but the food used to be more caloric, and sour cabbage and potato peelings were not enough for him.” His body was buried in a mass grave.

And, without even rising to his feet, he flew up into the air as he sat, and when he got above the house, he flew towards the trees. An extraordinary feeling of lightness took possession of him. For the first time he was flying in the open sky without a load. He suddenly became so excited that he was ready to sing and somersault in the air. Flying over an old jambolan tree, he seemed to dive in the air, picked some leaves on the fly and threw them, amused by this game. He flew up to a mango tree, made a circle over the large heavy leaves, descended lower and, hanging vertically in the air, began to pluck orange-yellow fruits the size of goose eggs, as if he stood on the ground and took them off the branches.

Alexander Belyaev, "Ariel", 1941When you read them now, Belyaev’s books seem naïve, almost infantile. The protagonists are all beautiful, young, bold, and noble. The antagonists are greedy, ugly, and often mad. Belyaev’s worlds are very clearly black-and-white. But maybe it is because the author’s personal world was so black, anything remotely gray seemed pearly-white to him.

What is hidden in his books is Belyaev’s astonishing strength of character. They are gentle, even tender. You would never guess from them the herculean tasks that their author had to overcome on a daily basis. He fought the state, his own frail body, his opprobrious fate. He fought hopelessly, with little chance of victory. And yet, there is no anger or despair in his books. There may be sadness, but the light and ethereal kind.

What his books are full of are dreams of movement, dreams of freedom, and dreams of flight.

For a similar (and also rather sad) story, I recommend my earlier post:

The desperate madness of Daniil Kharms

Hello, Russian literature has a reputation for being heavy, serious, and dark. This reputation is appropriate, but not all-encompassing. Russian literature is wide enought to allow goofiness, weirdness, chuckles, and outright madness.

Some shameless self-promotion.

If you’d like to support this journal and get an amazing anthology out of it, you can support us on Kickstarter

RIGHT HERE!

The anthology features works from nineteen incredible writers (and one from yours truly, which also is about people who can fly).

Best,

Ꙝ

Didn't know Belyaev's life was so grim and dark. Juxtaposition of it with his stories is even shocking, especially compared to the rest of Russian literature. Thank you for writing this sir

Amphibian Man is absolutely fantastic and Ichthyander is a very memorable protagonist.