Hello,

Rereading your favorite childhood book is somewhat similar to meeting your first crush at a 20-year high school reunion. They are nothing like you remember: somewhat slower, somewhat duller, somewhat heavier, definitely not as exciting to spend time with. Moreover, their personality seems to be completely different: small quirks that you found amusing and charming now seem like serious red flags, they are suddenly obsessed with politics—and what’s worse, their views are radically different from yours—and any traces of past levity, flirtation, and romance are gone.

This is what was going through my mind when I was recently rereading “The Three Musketeers”, a book that for a long time was in my top-five childhood treasures, whole passages from which I might still remember by heart, and that I revisited again and again, like many kids, wishing to be a part of it and including its characters in my daydreams.

Reading it now, in the second half of my thirties, left me with a wholly different experience, and an ambiguous one at that.

What changed? To be honest, the thing I least expected to change. I kinda hate the musketeers now.

You see, by any reasonable metric, neither one of the four main heroes is a good person. This is absolutely true for modern-day sensibilities. But this is also at least partially true for Dumas-day sensibilities as well, because at some of the most disturbing moments he does make an author’s remark, something in the vein of “yeah, you see, this behavior might seem bad to us, but trust me, in those times the morals were different”. I doubt they were, by the way.

First of all, it is important to say that all of them are murderers. Yes, they are soldiers, but that’s not what I am talking about. They kill quite a lot of people outside the field of battle, or even outside their jobs. I’m talking about duels. In the very beginning of the book, in rapid succession, there are several duels (declared as duels to the death) featuring our main character. The reasons for the duels are ludicrous: Rochefort mocked D’Artagnan’s horse; D’Artagnan bumped into Athos on the stairway and didn’t apologize well enough (!); D’Artagnan bumped into Porthos and saw that his baldric was fake leather; D’Artagnan tried to return Aramis his handkerchief; Bernajoux mocked D'Artagnan's ball-playing skills. None of these seems like a good reason to kill anyone. Given the musketeers’ constant money problems, they seem to deserve the title “murderhobos” more than most DnD players. But let’s approach this systemically and look at our heroes one by one, from least to most despicable.

Aramis is sort of okay, maybe because he is the most mysterious of the musketeers. He is a lover of a very influential and controversial woman and is probably very involved in her intrigues, but we don’t see him commit anything seriously bad except for the aforementioned occational murder. He’s also in a weird sort of denial about actually being a clergyman who deals in murderhobo-ing just temporarily as a way to pass the time (like any multiclass character (sorry, no more DnD jokes)).

Porthos is a simpleton and a buffoon, which is often explicitly pointed out by his friends. That does not make him an endearing character, but that’s at least not morally problematic. Somewhat more annoying is that he is also a gigolo: he extracts money from an older married woman, seducing her and leading her on. That results in one of the funniest scenes in the novel, but it's still kind of unpleasant to think about. In the sequel, she passes, and he inherits her husband’s fortunes, treating the whole story as a well-deserved retirement.

Athos is straight away a drunkard and a self-proclaimed misogynist, but for a while he seems decent, even noble, because of the effect he has on the main hero. But the reveal of his dark mystery is a blow to this reputation. Several years prior to the beginning of the novel, Athos was an aristocrat in love. He married a beautiful girl who was sixteen years old. During the hunt, she was thrown off her horse, and while helping her, he saw that the girl was branded as a thief. Without asking much about the circumstances of this unfortunate development, he stripped her naked and hanged her on the nearest tree. It probably took him less time than it took me to finish this sentence. I cannot look past that anymore when I think about Athos. This level of horribleness is only surpassed by…

D’Artagnan. Yes, he is the protagonist of the story, and we see a lot through his own eyes, but that only makes the things he does even harder to stomach. Let’s focus on the worst incident, after which it’s hard to look at our naive and hot-headed hero in the same way. It happens somewhere in the middle of the book, and no feat of gallantry and valour he does afterwards compensates for that. So, D’Artagnan sees a woman he really wants. (In fact, at that point in the book, he is already in a relationship with another married woman, but her husband is stupid and ugly, so it’s not considered adultery, and she is kidnapped, so he sort of forgets about her altogether.) But he sees a beautiful lady, and is immediately taken with her. He follows her, sees her talking to a man, and inserts himself into this conversation, which eventually leads to a duel. He fights the man, defeats him, spares him, and is introduced to this lady of his dreams (the man turns out to be her brother-in-law, which made yet another duel that led to several deaths completely moot). She is not very impressed. D’Artagnan is offended, so this is what he does. He a) seduces this lady’s maid, Kitty; b) using this poor girl (and breaking her heart in the process), he steals the lady’s letters that she wrote to yet another man, des Wardes (whom he wounded in another duel, for unrelated reasons); c) pretending to be des Wardes, he emotionally manipulates the lady; d) still pretending to be des Wardes, he visits the lady at night, sleeps with her, and then breaks up with her; e) as himself, he continues to manipulate her, promises to kill des Wardes, and sleeps with the lady again; f) when all is revealed, he is sort of surprised when it turns out that the lady isn’t that fond of him anymore.

The main hero of one of my favorite childhood books is a rapist and a sociopath.

But even that’s not all. Our merry band of murderhobos is not done. All their chivalrous quests, all the intrigues they were playing a part in—all of these were, in fact, real historical events. And there were instances throughout the book when the heroes appeared on the… strange side of history. Again, I will look at a single example.

The city of La Rochelle is under siege by the French king (it’s a religious thing; these were much more common in the past… oh, wait…). The musketeers are serving in the king’s army. The English are supporting the La Rochellians in their war, and the Duke of Buckingham is about to send reinforcements to help the city lift the siege. Cardinal Richelieu hatches a plan to murder the Duke: La Rochelle would lose their strongest supporter, and the city would fall. But the musketeers learn about this plan and send a letter to warn the Duke. I am not a historic law expert, but this seems like at least light treason to me.

Oh yeah, and in the end, they just sort of murder a woman in cold blood.

The whole last part is 100% true, and yet, I’m ashamed to admit, I really enjoyed reading this book. In fact, I liked it so much that I read the sequel immediately after (it’s both better and worse at the same time). After days of analysis and self-reflection, I can finally say what I did like about this book and why you should read it, even though all its main heroes are shameless bastards, and not in a good way.

First of all, Alexandre Dumas is a really good writer. He can be funny, can be fast-paced, can be epic, can be romantic, and, more importantly, he knows exactly when to switch from one to the other. He is also a master of blending historical reality with a made-up narrative. We know that the murderer of the Duke of Buckingham in the real world, for example, was called Felton, but when we meet him in the book, we are still surprised when (and why) he does it, and the intrigue is preserved.

Second, the musketeers are unpleasant people, but they are still great friends to each other. This aspect of friendship, of camaraderie and mutual love is so strong that it partially redeems all the misgivings. I think I managed to pinpoint exactly how Dumas makes it work. You see, in the world of the book, even a slight suggestion of mockery is a cause for a duel to the death. In the beginning of the novel, D’Artagnan was nearly killed for apologizing too hastily. However, after they become friends, the quircky quartet bicker, mock and deride each other mercilessly, and immediately laugh it off. And they get more and more relaxed about it throughout the whole narrative, like real people would. Dumas is sneaky and masterful about this change, and this is, in fact, almost the only character development these four get, which makes me think that it was the whole point.

And third, we come to the true jewel of this book. As we know from comic books, heroes are made by their rogue galleries. “The Three Musketeers” has, appropriately, three main villains: there is Rochefort, who has only a few lines and is basically a plot device—just a reason for D’Artagnan to run out of the room screaming, “The man from Meung!”. There is Richelieu, who is a plotting mastermind kind of villain and does not get his hands dirty. And then there is Milady.

I am fairly sure you’ve read the book, so you already know that the girl hanged by Athos, the lady wronged by D'Artagnan, and the woman they all killed at the end of the book is the same character. And what a character she is! Brave, smart, capable, extremely adaptive to every situation. She is a spy working for Richelieu—working for her own country’s benefit, I might add, unlike some murderhobos I know!—and she uses every tool in her arsenal to achieve her goals. She lies, steals, seduces, manipulates, and murders. She is On His Majesty’s Secret Service, with a literal License to Kill, and she Only Lives Twice! She is James Bond before James Bond.

I have a suspicion that is wholly unsupported. I think Dumas initially thought of her as a villain, but as the book progressed, he started to like her and think of her as one of the protagonists. That’s why, in the second half of the book, there are suddenly ten chapters written from her POV. And this is the best stuff in the book! Milady is captured by her enemy days before the deadline of a crucial mission. The enemy knows her well: he puts her in a perfect prison, designed specifically for her. And then, just by using her ingenuity, abilities, and character, she not only manages to escape but also to completely succeed in her mission! It is by far the most amazing thing anyone attempts in this book. These ten chapters redeemed the novel for me, even if they couldn’t redeem its characters.

The problem of Milady, as I continue to baselessly conjecture, is that the novel was originally published in a newspaper (an old-timey Substack) chapter by chapter. You see, he couldn’t edit it! Throughout the whole book, her “villainy” was pretty mild: she hired some goons to kill the musketeers, and then she poisoned their wine. Big whoop! Given the overall merry muderhobo vibe, she could have easily made peace with D’Artagnan (like Richelieu and Rochefort did). But Dumas screwed up: the stuff D’Artagnan did to her was too despicable to be redeemable. She had to avenge herself by doing something unforgivable in her turn, and then she had to die for it. But that’s why we have got one of the best villains in literature. And she elevates the rest of the book. She’s so good, in fact, that she could have made a much better protagonist than a horny, bloodthirsty teenager. From now on, to me, the true story of the three musketeers is the story of Milady.

Rereading your favorite childhood book is somewhat similar to meeting your first crush at a 20-year high school reunion. They are nothing like you remember, but it doesn’t have to be a bad thing. If you spend some time with them, you might learn that their image that you kept in your memory since your youth, washed away by time like a piece of ice in a slowly warming drink, was never true at all. But the reality is still interesting, deep, and engaging.

You might not fall in love all over again. But you might have found a friend.

This essay was originally written for

‘s brilliant Books That Made Us substack that has since transformed into not less brilliant APOCRYPHA substack.Best,

Ꙝ

Could not agree more that the Milady captivity chapters are a highlight of the book. When I first read Scott Alexander's stuff about the superintelligent AI god basilisk cajoling us into letting it out of its cage, that's where my mind went.

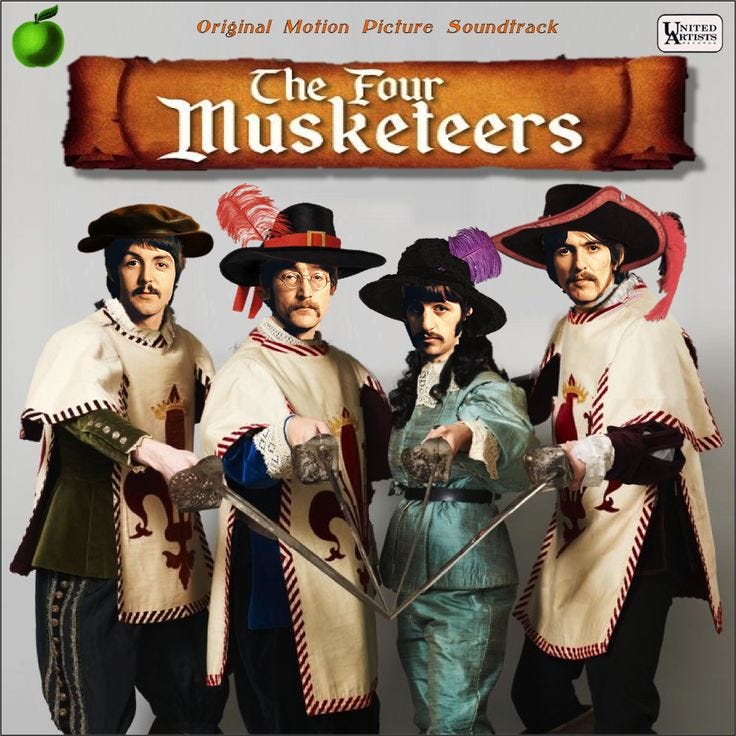

You touched a little on it in passing but an important part of the puzzle is that the Muskeeters are teenage boys, what they really need is two hours detention and a shower, not to be handed live weapons. Which the multiple adaptations have blurred by regularly casting actors in their late twenties or older, and which wafted back into the perception on the novel (the guys on the book cover you posted aren't teenagers, and they're far from the worst I've seen).

Indeed the end of the novel is largely a condemnation of the four men and a vindication of Richelieu, where the three secondaries are sentenced (by the narrative) to become grown-ups, and D'Artagnan gets sentenced (by the Cardinal) to become something even worse, a grown-up with responsabilities. Which is explicitly framed in terms in "now you'll see it feels to deal with a bunch of jokers nominally under your orders".

Unrelatedly adaptations are also responsible for a type of soldier literally named after a firearm to become associated with swordplay in the public consciousness. In Dumas, they do make use of gunpowder!

Loved reading this for the second time, as did for the first.

still vehemently disagree on a lot of it, being closer to "Milady"-but it's fun, all in all. To disagree on things like that. To read books together, in a way.