Hello,

This is a long essay about charlatans and the nature of science. I wrote it some time ago in Russian, and it was even partially published in a Russian-language journal, the link to which I will refrain from openly sharing for pseudonymity reasons. The current English version is approximately twice as long, updated, and unabridged. I will publish it in four parts, and this is part three. You can find part one here, and part two here.

***This is a long post that will be truncated into emails. I highly recommend you click on the title to read the whole 4500-word post without interruption.***

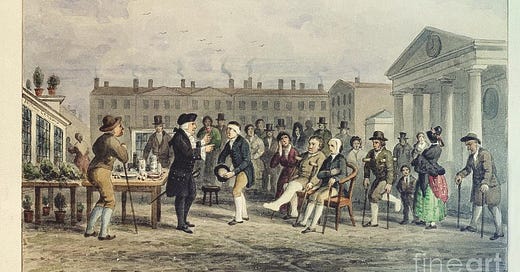

Thomas Hosmer Shepherd, “The Quack Doctor”

Scientific Charlatans and Where to Find Them, Part 3

“Certainty, not data, is knowledge.” — Ron Hubbard

4. Charlatans of the Mind

The world is full of loonies. Probably, almost everyone is one, to some extent. But among them, there are those who are more distinctly mad. Among these distinctly mad folks, there are those who consider themselves scientists. And then there are those who believe them. I'll try to tell you about these two groups. I've tried to select the most interesting examples from the hundreds available. Moreover, I aimed to present them in a way that allows for drawing analogies with the cases we already know from the previous part and to compare the madmen with the fraudsters. Let's start with the relatively harmless ones.

4.1 Kauko Armas Nieminen

Kauko Armas Nieminen might well be considered the academic equivalent of a street madman. A self-taught individual who once, long ago, earned a bachelor's degree in law, he nonetheless calls himself a physicist. His first book, "Eetterin fysiikkaa", which might mean "Physics of the Ether" (I'll leave it to experts in Finnish to correct me), was published in 1980, and since then he has written fourteen more. He doesn't use commercial publishers or advertising agencies, but prints and distributes his books independently. Judging by the picture on Wikipedia, he sells them right on the street. And although he's probably one of the hundreds of followers of the long-debunked ether theory, I personally find him somewhat endearing. Although, aside from scale and ambition, he essentially doesn't differ from Shipov and Akimov.

4.2 Brinsley Le Poer Trench, the 8th Earl of Clancarty, the 7th Marquess of Heusden

In choosing a mad ufologist, I won't lie, I was guided by the name. Really, they're all the same. They all have absolutely identical assertions, identical ideas, and identical thoughts. If you've heard one ufologist, you've heard them all. But the 8th Earl of Clancarty, firstly, is a nobleman, and secondly, a rare... well, how to put it simply. In one of the laudatory articles dedicated to him, he is described with the wonderful phrase "open-minded skeptic". Let's stick to this definition going forward.

Lord Trench, firstly, believes in aliens, and secondly, in the so-called "hollow Earth" theory. In the Earl's mind, these two theories merged into one. That is, he believes in aliens that came from beneath the Earth. I'm not joking! In his book "The Secret of the Ages: UFOs from Inside the Earth," he writes: "It is my firm view that the groundwork has now been prepared for a takeover of this planet by those who live inside it". Or, for example: "I still firmly consider that some UFOs come from other worlds in our physical universe and some from invisible ones, in another order of matter too. Some too, may come from bases under the sea…"

Laughter aside, with his title, this man has made quite a few moves. He had, among other things, a seat in the British Parliament and spent nearly thirty years demanding the British government declassify all secret documents regarding UFOs from beneath the Earth. Because the authorities are hiding something. Moreover, he organized a "UFO Study Group" in the House of Lords, ardently supported the ideas of Erich von Däniken, and occasionally engaged in lively debates about UFOs in the House of Lords. How he must have annoyed them.

Brinsley Le Poer Trench, a man with a funny name, an Earl, a Marquess, and a member of the House of Lords, an “open-minded skeptic” who sincerely believed in flying saucers, flying cigars, the origin of humans from aliens ("otherwise, how can one explain the different skin colors?"), a hollow Earth, Biblical Adam and Eve living on Mars, and much other nonsense — died in 1995. All his great discoveries and achievements were made in the sixties and seventies.

4.3 Devaneya Pavanar

Devaneya Pavanar was a renowned Indian writer, poet, and musician who wrote in Tamil. Tamil is one of the classical Indian languages, used in the southern part of the country. It has its own script, literature, a rich history that spans over two thousand years, and belongs to the Dravidian language family. They are spoken by about two hundred million people in total, with Tamil alone spoken by about seventy million.

The reason I'm dedicating so much time to Tamil is as follows: Devaneya Pavanar, a Tamil teacher by education, believed that Tamil was the original language from which all others derived, and that a civilization speaking and writing in it existed two hundred thousand years ago. According to Pavanar, these were the Lemurians. Devaneya Pavanar kicks off a series of stories about a special kind of “linguofreaks”. There's a great multitude of them, and I'll only tell you about some that seemed most interesting to me.

Linguistics is a science too. We can talk separately about why I consider it a proper science (and, say, literary studies, not). Some people might not agree with me here. There's a wonderful article (actually, more than one!) by professor A. Zaliznyak that I will frequently and eagerly quote. For now, I'll just say that the reason for such an unprecedented number of charlatans in this field is that, apparently, it's easier to cheat in linguistics. We'll talk more about this later, but let's get back to Pavanar for now.So, Pavanar believes that there was a wonderful continent called Lemuria, a huge landmass in the Indian Ocean that connected India, Madagascar, and Australia. This landmass housed the now-submerged state of Kumari Kandam, whose inhabitants spoke Tamil and were bearers of the great and lost Tamil culture. This was—chronology is always the weak point of all linguofreaks—about fifty thousand years BC. The people living there were called Tamilians, or Homo Dravida. In the fifteenth century BC, Lemuria, like Numenor, sank underwater, and since then, there has been no sign of it.

In reality, Lemuria is yet another of the beautiful scientific mystifications for which the nineteenth century is famous. It was indeed named after lemurs — silly wide-eyed creatures. In 1864, zoologist Philip Sclater invented a hypothetical continent connecting Madagascar, India, and Australia to explain the found remains of lemurs on all of them. No such remains were found in Africa or the Middle East, and Sclater needed an explanation for this phenomenon. The explanation itself was not bad — geology then was not sufficiently developed, and the concept of tectonic plates were unknown. Later, of course, it was debunked, but Lemuria itself remained — in the hearts and minds of the enlightened. For instance, Helena Blavatsky was a big fan of Lemuria. Of course, the word itself sounds beautiful and mysterious: the Lemurian priest Moradita, the golden dragon, the sacred word "Om", all that - but let's not forget that Lemuria is indeed named after wide-eyed lemurs. But enough of lyrical digressions — back to Pavanar.In 1966, he wrote a book, "The Primary Classical Language of the World," where he presented his arguments—for Tamil and, mostly, against Sanskrit. In terms of persuasiveness and substantiation, the arguments don't much deviate from "Tamil is more beautiful." No, I lie—an entire chapter in the book is titled "Tamil is more sacred than Sanskrit."

One of the annotations on his book reads: "It was a matter of surprise when the scientists came forward to split the atom. Now it has become a matter of much more surprise when Pavanar came forward to split the root of words until the origin of human speech. [...] His Primary Classical Language of the World is an eye-opener for the linguists regarding the mother tongue of man." How many more of these eye-openers there will be, is unfathomable. We’ll be looking like lemurs ourselves in no time.

4.4 Ido Nyland

Only a few words about this one—it's just too amusing to skip him. Ido Nyland, a Canadian of Dutch descent with a background in forestry, believes that all languages in the world originated from... Basque! To be precise, initially there was only one language—correct, Basque. Then, over several centuries, Benedictine monks—I'm not making this up—created all the other six thousand or so languages. Because—again, not making this up—"Let us go down, and there confound their language, that they may not understand one another's speech" (Genesis, 11:7). So, they took this as a call to action. Benedictine monks. Basque!

You can find his book "Linguistic Archaeology" online. His method is very simple—he takes any word from any language, breaks it into syllables, and adds letters to the syllables to make them into Basque words. For example, the word ‘begin’ is broken down into ‘be-egi-in’, which in turn is transformed into ‘ibe-egi-ino’, and from there into ‘ibeni-egindura-inor’, which means "to start-action-someone" in Basque. See, how trivial? It's pointless to argue with this. It's pointless to deny it. Ibeni egindura inor.

One question haunts me: why Basque, of all languages?

4.5 Anatoly Fomenko

This is a fairly well-known name. As with torsion fields, the main uproar regarding Fomenko's theories has already passed, but it would be unforgivable to overlook him in this review. I also pondered for a long time in which of the two groups to include him—"of the wallet" or "of the heart". As you can see, I've placed him in the latter, despite the more than sixty published book titles listed on Fomenko's official website. These books, with rare exceptions, are published in minimal editions, and their total circulation does not exceed one million. He's no Erich von Däniken—it’s a completely different level of reach. Though the nonsense is no more plausible.

Fomenko's main work, along with his usual co-author G. V. Nosovskiy's "New Chronology and Concept of the Ancient History of Russia, England, and Rome," is thoroughly and entertainingly dissected in the article "Linguistics according to A. T. Fomenko" by professor Andrey Zaliznyak (whom I’ve written about in another post). I will abundantly quote from it and his other articles, trying to select the most interesting moments, because I have nothing to add to the article. The main propositions of Fomenko's theory, as well as his main methods, aptly noted by Zaliznyak, are perfectly described by Nikolai Gogol in “Diary of a Madman”: "I discovered that China and Spain are absolutely the same land, and only out of ignorance are they considered different states. I advise everyone to write Spain on paper, and it will turn out to be China."

For Fomenko, it all started with Thucydides. The ancient Greek historian in his "History of the Peloponnesian War" describes three eclipses—two solar and one lunar. These descriptions allowed scholars to refine the date of the war's start. The problem is that according to astronomical calculations, one of the eclipses was partial, but from the Russian translation of Thucydides, one could understand it was total. This discrepancy was noted by Russian scientist and revolutionary N. A. Morozov at the beginning of the twentieth century. Well, Fomenko noticed it too. The fact that the original Thucydides describes the correct, partial eclipse did not interest Fomenko. The gargantuan conclusions he drew from this silly mistake would be called far-fetched by polite Englishmen and bullshit by rude Americans.

It's pointless to consider the entire legion of linguistic absurdities by A. F., of course. Let's limit ourselves to just a few. Here's the reasoning by which the authors of the New Chronology support their thesis that London was previously located on the Bosporus: "We believe that originally the River Thames was called the Bosporus Strait... Regarding the Thames, we add the following. This name is written as Thames. Events occur in the east, where, among others, Arabs read the text not from left to right, as in Europe, but from right to left. The word 'strait' has a synonym ‘sound’. When read backward, it becomes DNS (without vowels), which can sometimes be perceived as TMS—Thames" ["NH 2: 108"]. ("Linguistics according to A. T. Fomenko", A. A. Zaliznyak)

In essence, Fomenko rewrote all of history anew, drastically shortening and cutting it to his understanding. There's no scent of science here—instead, there's indeed an impressive imagination. The methods he uses—the apparent (and very often far-fetched, as in the case of the Thames) similarity of geographical names, so-called "dynastic parallelisms," the essence of which is that there are rulers who ruled a similar number of years (which is quite natural), and the grand theory of universal falsification of written monuments. At a glance, the "scientific" nature of his methods induces nothing but bitter laughter.

The logic is as follows: “The phenomenon P sometimes occurs in roughly similar cases, doesn't it? Why not assume it's the case in our situation?" The corresponding scientific discipline has long determined under what exact conditions P occurs. But A. F. does not wish to know this: it would deprive him of freedom of thought. In arithmetic, it would look like this: "The square of a number often ends with the same digit as the number itself, right? Here, 1×1 = 1, 5×5 = 25, 6×6 = 36. Why not assume that 7×7 = 47? ("Linguistics according to A. T. Fomenko", A. A. Zaliznyak)

One of the reasons for his success is mathematics. Fomenko is indeed a mathematician, a professor, a prominent scientist, and a member of the Russian Academy of Sciences. But his approach to history and linguistics has nothing to do with mathematics. And indeed, with science, if it comes to that. It resembles a joke more than anything. But—sixty written books, many years of nonsense and idiocy—the joke dragged on and became more like madness. I don't think Fomenko started as a swindler, or rather, that he began as one. Apparently, he genuinely believed in this new chronology of his. Then, when it became more or less clear that his ideas were delirious, it was too late to go back, and everything was put on a commercial basis. These are, of course, my speculations, and nothing more.

What harm does Fomenko do? He confuses idiots and madmen who eagerly grasp any nonsense thrown their way—well, so be it. In the end, smart people will understand that Germany and Assyria are two different countries, and Ivan the Terrible was not four people, but one. But this is not the only problem with Fomenko. Each such quack and madman inflicts irreparable damage on both the science from which he came and the science into which he entered. And that's very sad.

That A. F. offers a flawed concept of history—it’s not the main issue. It's a minor sin. The problem lies elsewhere: in the current era, when the classical scientific ideal is already under unprecedented pressure from irrationalism of all kinds, including clairvoyance, divination, superstitions, magic, etc., A. F., shamelessly using the full power of the traditional authority of mathematics, instills in young souls the idea that in the humanities there is essentially no positive knowledge, but there is a lot of deliberate falsifications, and one can freely oppose any statement of these sciences with one's intuitive guess. "I'm sure the word Moscow comes from the English "moss" + “cow”, i.e., "a cow in the moss"; "In my opinion, the original inhabitants of South America were Russians"; "My hypothesis: Peter the Great was a woman"; "My guess: Nicholas II and Leon Trotsky are the same person". None of these statements is worse or better than those presented by A. F. Any such statement now, inspired by the example of A. F., a young ambitious person can boldly present as a "scientific hypothesis," declaring the objectors to be dullards. As someone who deeply respects mathematics, I must say that hardly anyone has ever inflicted such severe damage to the prestige of mathematics and mathematicians in public consciousness as A. Fomenko. ("Linguistics according to A. T. Fomenko", A. A. Zaliznyak)

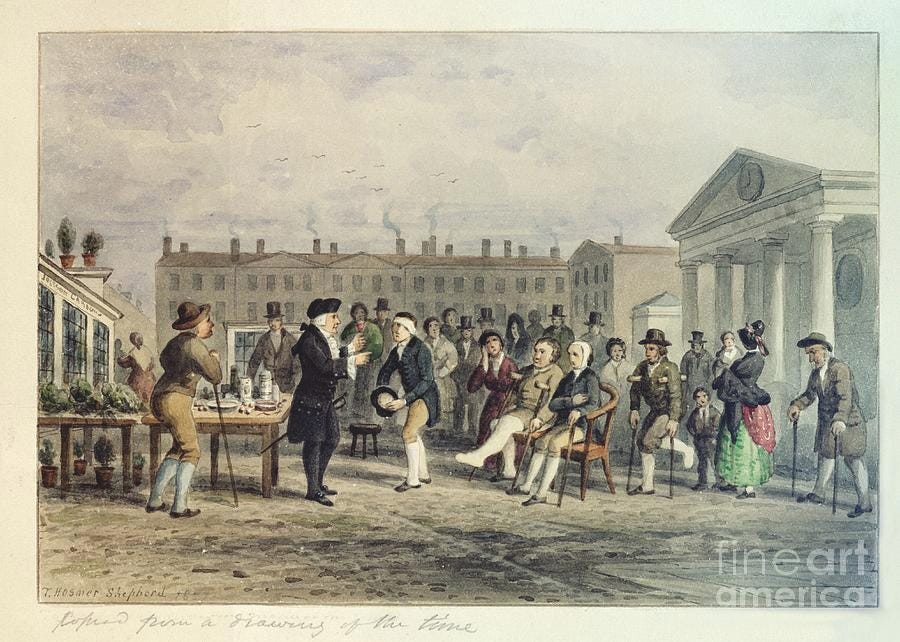

Francesco Sasso, “El Charlatan de Aldea”

4.6 Valery Chudinov

On the Internet, Chudinov is affectionately called "Grandpa Choo" or "Chuchundra". He speaks beautifully, convincingly, with emphasis, and loves giving interviews—a treasure trove of freak.

A very complete and detailed biography of Chudinov can be found online, so I'll just highlight a few key points. Chudinov is a physicist by education, graduated from the Physics Department of Moscow State University, and got his Ph.D. Somewhere in the mid-seventies, he began to take a serious interest in linguistics. This interest grew into a hobby, and the hobby became a life's work. Chudinov—by this time already a professor of philosophical sciences and a respected individual—definitely joined the ranks of linguofreaks in the nineties. That's when he began to read non-existent inscriptions, deciphering various random scribbles—first on monuments and historical artifacts, and then on anything at all. I write so much about him, because Chudinov is exceptionally generous with his own reflection; he describes his "discoveries" abundantly and openly. For example, here's his own description of his first "reading" of some scratches he found on a photo of an old spinning wheel:

I read this inscription with great interest as ‘ЧЕРЕВО’, noting that the part ‘РЕ’ was mirrored. I wasn't interested in why the spinner had scratched this word, but at that moment I felt like a pioneer. The word was READABLE! The first success exhilarated me, and I also read a few more inscriptions. And again, I wasn't interested in what all this could mean; I was overcome with a sense of flight, as if I had soared above the ground for the first time on a marvelous flying machine.

I suppose this feeling underlies the activities of many amateur epigraphists: a sharp sense of success where no one has tried to go before. The feeling of a pioneer. I achieved something, and I was thrilled with the result. I hadn't thought before that reading one or two words could bring such joy! Emotions literally overwhelmed me. (V. I. Chudinov, "My First Epigraphic Steps and Acquaintance with Ryzhkov and Grinevich")

These overwhelming emotions of discovery, apparently, played a role in his further fate. It seems that, like an addict chasing an easy high, he began to make more and more significant "discoveries"—until he lost his mind completely. Having gone through the entire difficult and sad path of Fomenko and many of his epigones, Chudinov went even further. I don't see the need to retell all his achievements in the field of science accessible only to him; I'll only mention a few of the latest ones. After reading large inscriptions in Russian on the ground and stones, visible only with the help of Google Earth, he determined that Russians lived on Earth long before all other peoples. But then similar inscriptions were found on the Sun, Moon, and Mars—obviously, the Russian language was brought to Earth by space envoys.

All these "discoveries"—inscriptions on the Sun, the secret language in Pushkin's drawings, the origin of all languages from modern Russian, Etruscan as a dialect of Belarusian, souls of the dead in photographs, the face of the god Yar in the fire of the World Trade Center towers—might seem funny. They are funny, grotesque in their absurdity. But they are, obviously, the product of a serious illness, perhaps "pareidolia" or "apophenia". This is not so funny anymore. Finally, as in the story about Fomenko, I'd like to quote a Russian classic, but this time not Gogol, but Chekhov, "A Letter to a Learned Neighbor":

I am terribly devoted to science! A ruble, this sail of the nineteenth century, has no value for me; science has overshadowed it in my eyes with its further wings. Every discovery torments me like a nail in the back. Although I am an ignoramus and an old-fashioned landowner, I still engage in science and discoveries, which I produce with my own hands and fill my ridiculous head, my wild skull with thoughts and a set of the greatest knowledge. Mother Nature is a book that must be read and seen. I have made many discoveries with my own mind, such discoveries that no reformer has ever invented.

4.7 Hanns Hörbiger

Going away now from linguofreaks, I'd like to talk about a few more notable charlatans and come to a sort of conclusion. An interesting case is Hanns Hörbiger, an Austrian engineer with a magnificent beard. He is a bona fide inventor—he authored patents on steel valves that are still sometimes used for high-pressure chemistry and metallurgy. His engineering company, Hörbiger & Co., was founded in 1925 under the management of his son, and it still exists! In 1925, Hanns Hörbiger retired from inventing and dedicated himself to scientific endeavors. Unfortunately, now he is mostly known for the latter and not for his truly remarcable engineering contributions to our world.

Hanns Hörbiger's claim to fame was the so-called "Welteislehre", or "World Ice Theory", also known as "Glacial Cosmology". The core of his icy idea is that ice is the basic substance of moons, planets, and the "global ether". He published these findings first in 1912 and heavily promoted them until his death in 1931. According to Hörbiger himself, he noticed that the moon was exceptionally shiny, and texturally resembled ice. Shortly after that, he had a dream in which he was floating in space watching the swinging of a pendulum, which grew longer and longer until it broke. "I knew that Newton had been wrong and that the sun's gravitational pull ceases to exist at three times the distance of Neptune," Hörbiger said. (I quote from the book "Watchers of the Skies: An Informal History of Astronomy from Babylon to the Space Age" by Willy Ley).

He quickly found a collaborator, an amateur astronomer, Philipp Fauth, who lent some credibility to his theories. Proper astronomers, understandably, did not buy his ideas. Hörbiger was steadfast. When told that his equations were wrong, he said, “Calculation can only lead you astray.” When showed high-resolution photos of the Milky Way, demonstrating that it is made of millions of stars and not, as Hörbiger stated, endless blocks of ice, he claimed that they were faked. Again, this man was a renown engineer! He could have known better.

After World War I, Hörbiger decided that the academic world was snobbish of his theories and started to promote them to the general public. Due to an interesting coincidence, one of his supporters was Houston Stewart Chamberlain, one of the ideologues of the Nazi Party. He passed them to Hitler and Himmler, who enjoyed "Welteislehre" very much and considered it a proper "Aryan" theory, unlike this pointless "Jewish science" with its quantum theory and atom splitting.

When Willy Ley, a scientist and science writer, wrote to Hörbiger that the surface temperature of the Moon exceeded 100 degrees under direct sun and therefore it could not have been made of ice, Hörbiger replied, "Either you believe in me and learn, or you will be treated as the enemy."

4.8 Immanuel Velikovsky

Immanuel Velikovsky was a renowned psychiatrist and Sigmund Freud’s pupil. He lived and studied in Edinburg, Moscow, Vienna, Berlin. He was one of the founders of “Scripta Universitatis”, a Jewish scientific journal, to which Einstein was a contributor. In 1939 he moved to the USA for a sabbatical that lasted the rest of his life. Inspired by Freud's Moses and Monotheism, he started researching a book called “Oedipus and Akhenaton”, in which he tried to prove that the Egyptian pharaoh was a prototype of King Oedipus.

That theory led him on a tangent. His ideas overall fit something he read in an ancient Egyptian papyrus, but the dates didn’t make sense; clearly, the problem was with the dates. He started to revise the chronology of Egypt, and that, in turn, necessitated revisions of world chronology and even astronomy in general. That led to a plethora of amazing scientific discoveries. Between 1950 and 1955, he published three of his main works, “Worlds in Collision”, “Ages in Chaos” and “Earth in Upheaval”. If you wanted to use these names for your fantasy novels—they are already taken!

What were his core ideas? I think his main drive was to correlate and equate biblical and other mythological events with real astronomy and geology. For instance, Noah’s Flood has analogues in other sources, such as the Epic of Gilgamesh or Plato's Timaeus. Velikovsky tried to reconcile this with real geological events. To do that, he had to invent some geological and astronomical events that are not recognized by the rest of the scientific community. So, for the explanation of the Flood, he suggested that Earth had once been a satellite of a "proto-Saturn" body, and the Flood had been caused by proto-Saturn's entering a nova state and spitting out Venus. A proof for the latter Velikovsky found in the myth of the birth of Athena from the head of her father, Zeus. The fact that Venus and Athena, and Saturn and Zeus, are all completely different deities, did not bother him at all. The fact that planets and mythological beings are not the same thing did not vex him one bit.

In addition, Velikovsky connected Mercury with the Tower of Babel destruction, Jupiter with Sodom and Gomorrah, and Venus, which he considered to be a comet, with “So the sun stood still, and the moon stopped, till the nation avenged itself on its enemies[…]” [Joshua 10:13]. Just like in astronomy, his revision of history started with his desire to reconsile biblical events with accepted historical chronology, and that led to him shuffling historical events like a deck of Tarot.

The scientific contemporaries didn’t like neither Velikovsky nor his ideas. In fact, they did not like them so much and attacked Velikovsky so vehemently that it was later studied as a case of overhyping that led to the propagation of faulty ideas rather than their quenching. The whole story was called "The Velikovsky Affair". The conclusion was—I am paraphrasing—that yeah, Velikovsky was a charlatan, and his ideas were loony, but the scientific community should take a chill pill and be a little bit more open-minded.

Of course, Velikovsky himself claimed that such a harsh rebuttal of his ideas made him a "suppressed genius" and likened himself to Giordano Bruno, as they often do.

Among the reasonable critiques of Velikovsky’s ideas, one has to mention James Fitton, who wrote in his 1974 article:

In at least three important ways, Velikovsky's use of mythology is unsound. The first of these is his proclivity to treat all myths as having independent value; the second is the tendency to treat only such material as is consistent with his thesis; and the third is his very unsystematic method.

Fitton, James (1974). Velikovsky Mythistoricus. Chiron, I (1&2), 29–36.I can probably continue this list ad nauseam. We haven’t even touched the perpetual motion community, the Nibiru guys, or the Flat-Earthers. But I think these examples can be a rather nice foundation for the next—and last—part of this essay, where I will discuss not the pseudoscientific quackery but rather the science itself and how to distinguish one from the other.

Best,

K.

Super interesting as always, Konstantin. One question remains... where do you find all these freaks?

Actual theoretical linguist here. I'm astounded at how many of these are attempts at historical linguistics. They're all tin-hat level conspiracy theories, but it's interesting how many cranks think they've discovered connections between totally unrelated languages, or decided that their native language is the 'ur-language'.

This seems particularly common among Tamil speakers--I get tons of Quora questions about how Tamil is the origin of Sanskrit, which is like saying Hebrew is the origin of Latin. Of course in the seventeenth century respectable scholars also believed the latter.

I guess the idea is that 'if you speak a language you're an expert on all languages'. Sigh...