Hello,

This is the first story that I wrote after moving from Israel to Germany, and I think one can see the nostalgia between the lines. I probably wanted to write something authentically Israeli. I remembered myself walking past the sambusak stand near the bus station in my home town—and that was the beginning of the story. I would not presume

to read this, but if he ever does, that would make me happy.I translated it from the original Russian (will open a pdf file) for the Soaring Twenties Social Club (STSC) Symposium. This month’s theme is “Habit”.

Mathematics

Rahamim Saroni's entire life was governed by mathematics. It occupied his thoughts and subconscious, shaped his actions, words, and emotions. At times, it appeared to him as an abacus, akin to the one his father Salah used in his shop, encased in a delicate frame but with heavy wooden beads darkened by time and grease. The beads would make a deep, hollow click inside Rahamim's head every time someone purchased a sambusak, and that sound wove itself into the rhythm of his existence as naturally as the noise of cars, the ticking of traffic lights, and the buzz of people crossing the street.

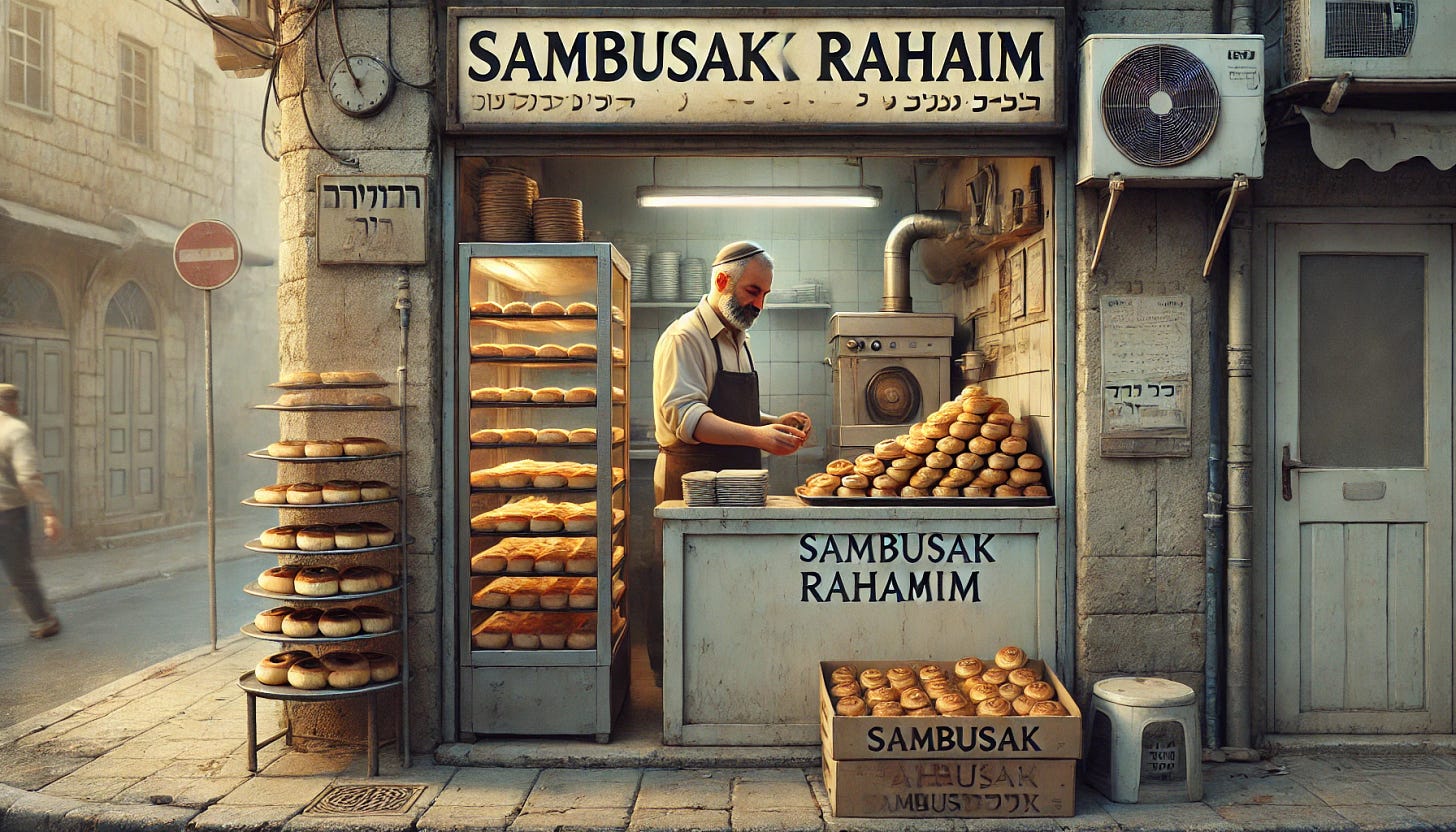

Sambusak is a pastry sealed on all sides with a savory filling enclosed in a thin, firm dough, a distant southeastern cousin of a calzone. After the death of Salah the Cobbler, Rahamim inherited his shop on the corner of Herzl and Jabotinsky, not far from the central bus station. It was a small, unattractive, and grimy one-story hovel. Rahamim, then still married and portly, 'invested': he repainted the walls, installed a large gas oven that resembled a wood-fire one, and paid an artist for a beautiful sign that read 'Sambusak Rahamim'. Every morning Rahamim took out a fresh batch of pre-cooked sambusaks from the freezer and lovingly sorted them into specially labeled boxes: 'sambusak potato', 'sambusak tuna', 'sambusak egg', 'sambusak double cheese', 'sambusak pizza', 'sambusak classic', 'sambusak hit', 'sambusak bomb'. As he placed each portion of pastries into the corresponding box, a continuous stream of mathematics flowed through Rahamim's mind: potatoes cost one shekel and seventy agorot per kilo, enough for twelve pieces, plus twenty-four agorot for the dough, plus gas, plus electricity, plus water, plus thirteen shekels per hour for wages, plus... This stream foamed against the dam of the price tag above the box, a number significantly higher than the cumulative value of everything that flowed downstream, and with every purchased sambusak, a bead on the abacus in Rahamim's mind satisfyingly clicked.

‘Sambusak Rahamim’ was open twenty-four hours a day, six days a week. On Saturdays, there were no buses, and the flow of customers from the station subsided, so it wasn't too difficult to observe Shabbat, but still, every Friday evening, as he closed the iron shop curtain, Rahamim felt a void. He disliked when the abacus fell silent and feared that, for some heavenly or earthly reason, he would no longer hear that cherished clicking sound. Rahamim was working in the shop every day, for about twelve to fourteen hours. During the rest of the time, young boys took turns working at ‘Sambusak’, either having just finished their studies or their army service; sometimes even high school students skipped classes, looking for a quick and easy job. Rahamim's own children also worked there for a while, but they grew up, joined the army, then moved up north, and lost interest in ‘Sambusak Rahamim’, and Rahamim's interest in them, correspondingly, faded away.

Rahamim's life was going well. The location was prime, there were many customers, and the enticing aroma of heated sambusaks wafted from the oven, reaching all the way to the exit of the bus station when the wind was favorable. Thus, Rahamim easily outperformed his main competitors, ‘Burger King’ and ‘Sbarro’. The tables at the latter establishments were mostly filled with youngsters celebrating their never-ending birthdays. Serious people occupied the three plastic tables at Rahamim's shop—workers from the nearby construction site, market vendors, and soldiers awaiting their buses. Rahamim had regular customers as well—wise locals and retirees—but the majority of abacus clicking came from bus passengers. During peak hours, the abacus unleashed veritable barrages of rapid clicking.

The key to Rahamim's success, his secret weapon, was Ima-le. Her real name was Shoshana, but somehow it got forgotten over time, and everyone, including strangers, simply called her ‘Mommy’—Ima-le. She was Rahamim's mother-in-law. She lived in a small one-bedroom apartment not far from ‘Sambusak Rahamim’, and every single day, all day long, she prepared sambusaks. Ima-le produced between thirty and forty sambusaks daily, including Saturdays. She par-cooked them in a small electric oven and stored them in a gigantic freezer. As an employee, Ima-le was far from perfect: her arthritic hands kneaded and rolled the dough too slowly, the sambusaks occasionally opened up and bled out their filling, and the filling itself often turned out undersalted. But she was willing to work contentedly around the clock, demanding nothing from Rahamim except paying her house bills and the occasional restocking of ingredients. Ima-le was a short, sturdy, hunched cornerstone upon which the entire sambusak empire rested. Rahamim understood this well, and every time Ima-le complained of feeling unwell, he would leave the shop to one of the youngsters, drive her in his worn-out Peugeot to a familiar doctor, help her out of the car with great care, and then wait restlessly on an uncomfortable chair, deep in his mind seeing the abacus beads scattered on the reception floor.

The trouble came from where Rahamim least expected it, although he always had a bad hunch. On an April Sunday morning, the radio informed Rahamim that the day would be warm but not hot, which meant that all three tables would be occupied and the philosophical conversations of the regulars would last much longer than the lunch hour. This meant that he should expect extra clicking in his head, and this thought amused him as he went to Ima-le's place to pick up yesterday's sambusaks. He even noticed the children playing ball in the courtyard instead of going to school and remembered that the Pesach school holidays had begun. Grace descended upon Rahamim, who didn't like Passover because of the prohibition on leavened bread but loved the two weeks before it; during the holidays, children happily bought his sambusaks, flocking to the shop in groups, and even brought them to their parents.

“Rahamim, I want to go to Paris,” Ima-le said when he entered her small kitchen slowly and gracefully, like a king inspecting his armies. At first, Rahamim didn't understand.

“What Paris, Ima-le?” he calmly asked, taking out some sambusaks from the freezer.

“Well, Paris, in France. Mila told me…”

A wave of coldness ran through Rahamim's stomach. He always felt something between burning dislike and sobering fear towards Mila. Moreover, she was a ‘russiya’, that is, Russian, and Rahamim had no reason to like those. Mila herself was a plump woman of small stature and Ima-le’s neighbor. She worked as a nanny and often came to visit, distracting Imale from her work, which also never evoked any sympathy. Several times she brought ‘blinchiki’ – strange, soft and moist to the touch, lace-thin pancakes that needed to be topped with jam and sour cream. Rahamim liked ‘blinchiki’ even less than he liked Mila herself, for his was a savory empire and a savory mindset. Despite the small age difference, Mila looked significantly younger than Ima-le. She wore normal, non-’granny’ clothes and spoke with a loud, deliberate voice. At first, she and Ima-le were simply friendly, as neighbors make themselves out to be, but then they became genuine friends when, to Rahamim's dismay, it turned out they had many common interests.

“... and it's not very expensive, a week after Passover, so it's discounted, and Mila's daughter-in-law works in a travel agency…”

‘No, Ima-le,” Rahamim said. “It is impossible.”

Usually, his categorical tone was enough to convince Mommy of anything, but this time an unfamiliar spark ignited in her eyes.

“I need a vacation, Rachi.”

This name initially stunned Rahamim because no one had called him that in a long time.

“I work every day, constantly, and I've never asked you for this. And now I'm tired. The children also say that I need to rest.”

Bewildered, cornered, Rahamim couldn't imagine where Ima-le, who seemed to him a quiet and docile creature capable only of wrapping filling in dough, suddenly found desires, persistence, and a deadly, firm logic. The last thing she said to him yesterday was, “We ran out of tuna,” and now... Rahamim tried to discern notes of Mila's voice in Ima-le's—Mila was a teacher in the Soviet Union—or at least the authoritative tone of his eldest daughter, but no, it was Ima-le herself, calm and resolute. It was a pure shock to Rahamim, as if a dusty photograph of his wife had suddenly started talking.

“I'll think about it, Ima-le; we have to work,” he forced himself to say and quickly left the room. There was no trace of the April mood, and the abacus fell silent.

“What? Paris? Of course I've been to this Paris!” Nahum Zalboni rasped loudly when Rahamim shared today's incident with his regulars. Nahum pronounced the word ‘Paris’ in a French manner, ‘Pari’, and in his speech it seemed sudden, like a juicy raisin in a stale bun. “My grandson lives there. I visited him.”

Nahum was the patriarch of a giant clan that spread its branches across three continents. He had six children and twenty-seven grandchildren, and now great-grandchildren were starting to appear, with their numbers threatening to invade triple digits in the future. Nahum also loved mathematics.

“And what is there?” Rahamim asked. He tried to articulate the internal anxiety but only managed one word: “Dangerous?”

“Dangerous? Why would that be, all of a sudden?” Nahum laughed, and others laughed with him. “What can those Nazis do to us already?”

Nahum referred to all Europeans as Nazis.

“Nazis-shmazis,” his friend Eliezer, the owner of the tomato cart, chimed in. “What's there to see? What does she want there?”

“She wants what she wants.” Nahum concluded the conversation and sank his teeth into the sambusak.

Rahamim, however, was not convinced and went the next day to defend his position. Mila was waiting for him in Ima-le's apartment. She stood in the middle of the kitchen, firm and straight, barely reaching Rahamim's chest. Her eyes carried an expression he hadn't seen since elementary school.

“Tagid li, bvakasha, Rahamim,” she calmly said in her Russian accent, flattening the consonants and rounding the vowels. “You tell me, please, Rahamim, why do you not let Mommy rest? Mommy wants to go to Paris. Why do you not allow her? It is your family.”

“I don't have family there.”

“She! She is your family, and she wants to go.”

“But... Why Paris? What’s there?”

“It is…” Mila hesitated, searching for a word. “It is romantika.”

“Romantika,” echoed Ima-le from her kitchen chair, and the abacus in Rahamim's mind groaned as if the metal wires were poorly-tuned strings.

Together, they packed a small suitcase discovered on the shelves in Rahamim's apartment. The tour, arranged by Mila's future daughter-in-law, was in Russian, but Mila said she would translate, and most importantly, they would experience the romance without the need for words. Rahamim remained mostly silent, only trying to object once when Mila took Ima-le out shopping, but was quickly put in his place.

“Paris is fashion capital, Rahamim,” Mila said firmly. “Mommy cannot go there dressed like this.”

Throughout Passover, by prior agreement, Ima-le spent full days making sambusaks and storing them in the freezer. Her movements had a new levity, and Rahamim heard her humming to herself as she wrapped the filling in dough with an old aluminum spoon. On the holiday eve, Ima-le scrubbed the spoon to a pristine shine, catching the sunlight through the small kitchen window, adorning the walls with lively glimmers. Surprising everyone and most of all himself, Rahamim went to the synagogue and, on the third day of Passover, to the cemetery.

Rahamim himself drove Mila and Ima-le to the airport, entrusting the handling of ’Sambusak Rahamim’ to yet another nameless guy. The airport was crowded, queues moved slowly, and Rahamim had plenty of time to observe as two small women, talking about something of their own, slowly disappeared behind the gates, like the Israeli spring sun during sunset.

The following week was the worst in Rahamim's life since he, after eight months of pure hell, buried his wife in the narrow, overcrowded cemetery beyond the city limits. He himself did not realize it at first—business was booming, the sambusaks premade by Ima-le flew off the counter, and the abacus in Rahamim's mind obediently clicked, counting profits. He chatted eagerly with customers and even engaged in a lively argument with Nahum Zalboni about the prospects of the prime minister in the upcoming elections. But the sound of the beads in his mind was unfamiliar, dull, something was wrong, something broke, and Rahamim couldn't understand what exactly, nor could he even begin to try to understand. For the first time in many years, he started having dreams; initially strange and shapeless, as if he were just learning to have them. Then the dreams began to take form, but he couldn't remember them afterwards and woke up in the middle of the night in horror, trying to find his glasses in the pitch-black predawn darkness. He would lie down again, but instead of sleeping, his mind would start thinking, thinking, but in the end, couldn't focus on anything. The more he thought, the more uneasy he became, and the harder he tried not to think, the more relentlessly thoughts flooded his mind. During the day, he envisaged all imaginable and unimaginable disasters that could happen to Ima-le, her plane, her hotel, and the whole city of Paris. But she dutifully and plainly wrote him text messages saying that everything was fine, she liked the city very much, it was beautiful there, the trees were blooming, the fashion was stunning, and the food was delicious. She and Mila would stroll along the riverbank or go up the Eiffel Tower. Despite these short messages full of typos—he imagined her cautiously pressing the buttons of Mila’s old, worn-out phone with her ailing fingers—he didn't feel any better; if anything, he felt almost suffocated. One day, while wrapping another sambusak in a napkin and putting it in a plastic bag for a customer in a hurry to catch the bus, Rahamim suddenly remembered his father. Salah the cobbler, smiling, was repairing someone's shoe, while Rahamim himself, four or five years old, sat under the table watching him. Rahamim remembered every detail vividly: the heavy, sour smell of glue, the dust and shavings on the floor, his father's bare, calloused soles. A visitor entered—heavy, tired feet in leather sandals—and laughter and words of gratitude came from above. Salah leaned back on his creaky chair, reached into a drawer, and took out the repaired item. The visitor began inspecting it, and Rahamim's mother cautiously entered the workshop—her feet strangled by arthritis. She called Rahamim, he crawled out from under the table, took her hand, and followed her. The last thing he heard as the door closed was the urgent clacking of his father's abacus.

Then she returned. Mila's son met them late at night. The next day, everything returned to normal. The world regained its balance. Rahamim didn't go to Ima-le's place in the morning because there was nothing to pick up yet. Instead, he arrived at ‘Sambusak Rahamim’ early, turned on the gas stove. It became hot and comforting. When the first customer, Farouk the builder, who was repairing the wing of the bus station, approached, Rahamim was already sweating profusely. Farouk handed him a green note, received some coins as change, and suddenly the abacus in Rahamim's mind clicked so resonantly that he momentarily went deaf, dissolving in that sound, as if the long-tormenting earplug in his ear had dissolved. Another customer approached, then another. People were in a hurry to go to work. Rahamim barely had time to throw the sambusaks into the oven. He only managed to take a break around eleven o'clock, but soon the lunchtime diners arrived. All three plastic tables were filled with people. People stood, leaning against the walls, hastily eating the hot, oven-fresh pastries and quickly leaving for others to take their place. The flow subsided only around eight o'clock, and an hour later, Yossi came to replace Rahamim and work the night shift. Yossi had recently been discharged from the army and was saving money for a trip to India with his girlfriend. After exchanging a few words with him, Rahamim calmly headed towards Ima-le's house. Without rushing, catching his breath when needed, he climbed the narrow staircase to the fourth floor. He opened the door with his key. Ima-le was waiting for him in the kitchen. The light was bright. Rahamim joyfully entered, abruptly stopped, and a moment later, for the first time in his life, burst into tears. In the middle of the flour-covered table, neatly arranged on a plate, there were three ugly, ineptly made croissants.

This story was translated and published for the Soaring Twenties Social Club (STSC) Symposium. The STSC is a small, exclusive online speakeasy where a dauntless band of raconteurs, writers, artists, philosophers, flaneurs, musicians, idlers, and bohemians share ideas and companionship. Each month, STSC members share something around a set theme. This cycle, the theme was “Habit”.

If you are a writer, you might consider joining us.

Best,

K.

sounds a bit like ramat gan to me

🫠